September 15, 2005

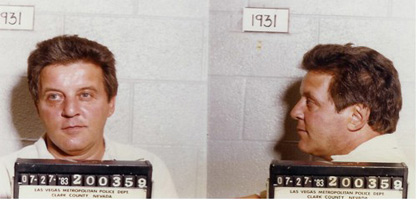

Tony Spilotro (Courtesy LVMPD)

The introduction to Griffin's book entitled The Battle for Las Vegas — The Law vs. the Mob. The book chronicles the wide-ranging, criminal exploits of Chicago Outfit enforcer Tony Spilotro, the mobster portrayed by Joe Pesci in the movie Casino, and law enforcement's belabored efforts to oust the Mafia from Vegas. It is told in large part by the former FBI agents and detectives who fought the war against Spilotro and his Hole-in-the-Wall Gang. The book is scheduled for publication by Huntington Press in early 2006.

Introduction

Mobster "Bugsy" Siegel is generally acknowledged as being the first member of organized crime to establish a major mob presence in Las Vegas. That occurred in the 1940s, when he took control of an unfinished hotel/casino construction project located on what would become known as the Strip. That property was the Flamingo. Siegel, financed with several million dollars of organized crime money from back east, saw the Flamingo through to completion. After a shaky start, the casino began to turn a profit. But some of Bugsy's financial backers had become suspicious of how he was spending their money. And the handsome, but volatile, gangster had shot his mouth off to some very dangerous people, including New York City boss "Lucky" Luciano. The Flamingo's improving financial picture wasn't enough to save Siegel from the mob's version of early retirement. On June 20, 1947, the 41-year-old was gunned down at his girlfriend's Beverly Hills home. Bugsy was dead, but the mob knew there was the potential to make some big money in Vegas. As the oasis in the desert transitioned into the gambling and entertainment capital of the world, more mobsters and their money poured in.

During those years organized crime considered Las Vegas to be an open city. Crime families from across the country were welcome to operate there, and many did. But the dominant group was the Chicago Outfit. In the 1970s, Chicago and its colleagues in Kansas City, Milwaukee and Cleveland were using Sin City as a cash cow. Commonly referred to as the "skim," unreported revenue from certain casinos was making its way out of Vegas by the bag full, and ending up in the coffers of the crime bosses in those four locations.

The skim involved large amounts of money, and the operation had to be well managed to ensure a smooth cash flow. To accomplish that goal, the gangsters had brought in a front man with no criminal record to purchase several casinos. Allen R. Glick, doing business as the Argent Corporation (Allen R. Glick Enterprises) purchased the Stardust, Fremont, Hacienda, and Marina. Then they installed Frank "Lefty" Rosenthal as the real boss. Rosenthal was a Chicago native and considered to be a genius when it came to oddsmaking and sports betting. He had been a good money producer for the Outfit for several years. However, he was forced to remain an "associate" of the family, because Jews were not permitted to become "made" men. Under Lefty's supervision, the casino count rooms were accessible to mob couriers. The skim was up and running the way the mobsters wanted.

However, the bosses weren't stupid, and didn't believe in leaving things to chance. They knew there were crooks out there always looking for ways to make a quick and dishonest dollar. Maybe having Rosenthal calling the shots inside the casinos wasn't sufficient to guarantee the integrity of their operation. What if an outsider tried to muscle in on the operation? Or just as bad, suppose one of their own decided to skim the skim? To guard against such possibilities, it was decided to send someone to Vegas to give Rosenthal a hand should that kind of trouble arise. The successful applicant had to be a person with the kind of reputation that would deter interlopers from trying to horn in, or make internal theft too risky to try. But if a fearsome reputation wasn't enough, action had to follow. In other words, the mob's outside man in Vegas had to be an individual capable of doing whatever it took to protect its interests. So, in 1971, 33-year-old Tony Spilotro, considered by many to be the "ultimate enforcer," his wife Nancy, and son Vincent, moved to Las Vegas. Tony was a made man of the Outfit and a childhood friend of Rosenthal's. The mobsters now had their bases covered.

Spilotro, sometimes called "tough Tony," or "the Ant," had the kind of reputation that would cause troublemakers to think twice before making a move on the Outfit's business arrangements in Vegas. He was known as a man who could be counted on to get the job done. Tony began earning that status a decade earlier as an enforcer for a Chicago loan shark named Sam "Mad Sam" DeStefano. Young Spilotro proved to be capable of committing acts of extreme viciousness. It was alleged that on one occasion Tony forced a man to provide information he didn't want to give up by placing the guy's head in a vise and squeezing until one of the victim's eyeballs popped out. This incident was depicted in the 1995 movie Casino, in which actor Joe Pesci played a character based on Tony Spilotro.

Spilotro was an ambitious sort, and quickly recognized that there were other criminal opportunities in his new hometown besides skimming from the casinos. Street crimes ranging from loan sharking to burglary, robbery, and fencing stolen property were all in play. It wasn't very long before Tony had his hands into every one of these areas. As the scope of his criminal endeavors grew, Tony brought in other heavies from Chicago to fill out his gang. His burglary crew was called "The Hole-in-the-Wall Gang," because of their method of entering businesses by going through the wall or roof. They also hit residences with equal relish. The five-foot-six-inch gangster was soon being called the "King of the Strip."

As the years passed, Tony and his activities became the main focus of both federal and local law enforcement. The feds were interested in getting the mobsters out of the casinos and stopping the skim. The locals were mainly responsible for investigating the gang's street crimes. It seems that this would have been a clear case for a well-coordinated, two-pronged attack by the law against the bad guys. But all was not well between the FBI and the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department. FBI wiretaps had caught Metro cops passing information to Spilotro and other mobsters. One detective, Joe Blasko, was regularly heard reporting the details of surveillance activities and information on potential burglary targets. In 1978, when Blasko's superiors learned they had a rogue cop on their hands, they fired him. But the resulting scandal cost Metro its credibility with other agencies and law enforcement groups. The bottom line was that their colleagues believed the local cops couldn't be trusted when it came to handling sensitive information or investigating organized crime. The FBI wouldn't involve Metro in their investigations. The two agencies went about their business working independently of each other. The rift was bad for law enforcement, but good for the criminals.

In November 1978, things began to change with the election of John McCarthy as sheriff of Clark County. McCarthy had run as a reform candidate, vowing to first clean up Metro and then declare war on organized crime in Las Vegas. Upon assuming office in 1979, Metro's new boss made wholesale changes in the staffing of the department's Intelligence Bureau. Although it took some time for trust to be restored on an institutional level, individual agents and detectives formed personal relationships rather quickly and information began to be shared. That was followed by cooperative investigations targeting Spilotro and his men.

Although law enforcement was getting its act together and the picture was improving from their perspective, the mobsters were worthy adversaries. The war between the law and the criminals ebbed and flowed, with victories and setbacks for each. On the mob side, Tony Spilotro had a strong advocate in the form of criminal defense attorney and future mayor of Las Vegas, Oscar Goodman. During nearly 15 years of investigations and indictments, Tony was never convicted of any serious charges.

What the lawmen needed to break the standoff was a decisive event that went in their favor, something that would drive a wedge between the gangsters and lead to an informant or a cooperating witness. That much-needed break occurred on July 4, 1981, when the HITWG burglars went after a million dollar score. Their target that night was a business called Bertha's Gifts & Home Furnishings on East Sahara.

The job was well planned by the burglars, but the lawmen were ready for them. Through excellent intelligence work, the authorities had a source inside the gang. They knew well in advance what Spilotro's gang had planned for that evening. As darkness settled in and fireworks lit up the sky over Las Vegas, the gang burgled and the law sprung its trap.

Bertha's

It was the Fourth of July and it was hot. It was always hot in Las Vegas in July, but to many of the 40 or so FBI agents and Metro officers working a special assignment, it seemed even hotter than normal. And that was only the temperature. If things worked out as planned, the heat would get even more intense for Spilotro's Hole-in-the-Wall Gang.

The center of the law's focus that day was Bertha's Gifts & Home Furnishings, located at 896 East Sahara. The store was in an upscale single-story building, and included a jewelry shop on premise. The lawmen believed a burglary was going to take place at that location in the evening, with the thieves expecting a take of around $1 million in cash and jewelry. That kind of haul was a big score, especially in 1981 money, and the HITWG crew that had been assembled to carry out the burglary reflected that. It was comprised of criminal stars Frank Cullotta, Wayne Matecki, the homicidal Larry Neumann, Leo Guardino, Ernie Davino, and former cop Joe Blasko.

Their opposition was headed on-scene by the FBI's Charlie Parsons and Joe Gersky, and Metro Lt. Gene Smith. Their bosses — Joe Yablonsky and Kent Clifford — were nearby, and available if needed to make any necessary command decisions.

Although the actual crime wasn't to take place until after dark, the lawmen were at work much earlier in the day. After weeks of preparation, the final planning had to be done, and a command post and necessary equipment needed to be set up. Surveillance teams were active around Bertha's all day, monitoring activity and making sure they were thoroughly familiar with the area. An eye had to be kept on the bad guys also, looking for any indication of a change in their plans or other potential problems.

With two different agencies participating in the operation, communications were particularly important. Their radios had to have a common frequency, but one that wasn't known to the burglars. A secret frequency was obtained and divulged only to those with a need to know. It was decided to utilize the regular frequencies, those likely to be monitored by the thieves, to disseminate bogus information as to the location and status of personnel. In the late afternoon the balance of the agents and officers deployed to the field.

The main observation point to observe the roof of Bertha's was from the top of a nearby five-story building. Charlie Parsons and Joe Gersky took up positions there, along with the equipment and personnel to videotape the scene. Gene Smith worked with the surveillance detail, riding with an FBI agent. The burglars were not to be arrested until they actually entered the building, making the crime a burglary rather than the lesser charge of an attempted crime.

It was believed that at least four vehicles would be used by the burglars, three of them to conduct counter-surveillance activities, and one to transport the three men who would go on the roof and do the break-in. Frank Cullotta, operating a 1981 Buick, Larry Neumann, in a late model Cadillac, and an unknown individual — possibly Joe Blasko — in a white commercial van with the name of a cleaning business and a "Superman" logo on the side, would represent the gang's forces on the ground. The occupants of all three vehicles would be equipped with two-way radios and police scanners. The burglars, Matecki, Guardino and Davino, would arrive by station wagon and go on the roof to gain entry to the store. They would also have radios to keep in contact with the lookouts on the ground.

At around 7 p.m. the HITWG counter-surveillance units began to appear. Cullotta and Neumann repeatedly drove around the area, apparently checking for a police presence or anything that seemed suspicious. In turn, they were being tailed by cops and agents. The white van took up a position in the driveway to the Commercial Center shopping plaza, across the street from Bertha's. From this vantage point, the operator — believed to be Joe Blasko — had an unimpeded view of the store. As the man in the van watched, he was under constant surveillance himself.

While this game of cat-and-mouse was going on, the whole operation almost came to an abrupt end. Gene Smith and the FBI agent were stopped at a traffic light when a car pulled up next to them. Out of the corner of his eye, Smith saw the driver of the other car was none other than Frank Cullotta. The cop − very well known to Cullotta − went to the floor of the vehicle as fast as he could. The light changed and Cullotta pulled away. It is almost a certainty that had Smith been spotted in the area the burglars would have scrubbed their plans.

At approximately 9 p.m. a station wagon bearing Matecki, Guardino, and Davino arrived and parked behind a Chinese restaurant located at 1000 East Sahara. A police surveillance vehicle was parked nearby, but went unnoticed by the burglars. The three men exited their vehicle and unloaded tools and equipment, including a ladder. They next proceeded to the east side of Bertha's and gained access to the roof, hauling their gear up with them.

From the roof a few buildings away, the videotape was rolling. The burglars were obviously unaware they were walking into an ambush. Utilizing electric outlets located in the air conditioning units, they went about their business, using power and hand tools to penetrate the store's roof. Everything was going pretty smoothly for both sides. Other than Lt. Smith's close call with Cullotta, the only thing that had gone wrong for the law so far was that one of the surveillance teams had to be treated for dehydration.

Agent Dennis Arnoldy was in charge of a four-man team, two FBI and two Metro, responsible for arresting the thieves on the roof. They relaxed as best the could in the back of a pickup truck in the parking lot of the Sahara Hotel & Casino, located a few blocks from Bertha's.

Arnoldy and his team weren't expecting their prey or the lookouts to be armed. These were veteran criminals, and they knew that if they were caught with guns the charges against them would be more serious, and the potential penalties would be greatly increased. The lawmen certainly hoped that would be the case.

As the burglars progressed in their efforts to get through the roof, Arnoldy and his men made their way to the scene. Using a ladder they got onto the roof. An impressive fireworks display exploded in the sky over Las Vegas as the lawmen secreted themselves behind vents and air conditioning units to wait for the pre-determined arrest signal to be broadcast. At that point a minor snag developed when the burglars broke through, only to realize they hadn't hit their target: the store's safe. Recovering quickly, they soon made another entry in the right place. At approximately 10:40 p.m. Leo Guardino dropped through the opening and into the store, carrying the tools necessary to break into the safe. The act of burglary was then complete.

Arnoldy, shotgun at the ready, heard a broadcast over his radio that he thought was the arrest signal. But due to the noise from the constantly running air conditioners he couldn't be sure. He hesitated for just a few seconds and then directed his team into action. When Davino and Matecki detected the lawmen approaching they scurried to the front of the building and possible escape. But when they looked down on Sahara they saw a number of agents and officers on the sidewalk below them pointing weapons in their direction. Knowing the game was up, they surrendered without incident. A few seconds later Guardino's head popped up through the hole in the roof and he was taken into custody.

On street level, other agents and cops were already busy apprehending the lookouts. Neumann and Cullotta were nabbed a short distance from Bertha's. Agent Gary Magnesen and two Metro officers arrested Joe Blasko. In a 2004 interview Magnesen recalled the incident.

"One of the Metro officers was in uniform and driving a black and white. Our plan was for the marked car to come up on the van from the rear with its lights flashing and headlights illuminating the van's interior. Another detective, armed with a shotgun, and I with a pistol, approached the van from the front and ordered the occupant out. Up until that point we thought it was Blasko inside, but we weren't positive. In fact, some of the cops didn't want to believe that their former colleague had really gone to the dark side. When Blasko got out the cop recognized him and said, 'Son of a bitch.' This was the best joint operation I was part of while in the Bureau."

No weapons were found on Blasko or any of the other arrestees.

When agents and officers entered the store they found that the gang's second hole in the roof had been accurate, and was located directly over the safe. Burglary tools were found nearby and several holes had been drilled into the safe in an effort to open it. Leo Guardino had been a busy man during his short time inside the building.

Joe Yablonsky and Kent Clifford held a press conference shortly after the arrests were made. They told reporters that Frank Cullotta, age 43, Joe Blasko, age 45, Leo Guardino, age 47 and Ernest Davino, age 34, all of Las Vegas, were in custody. Also arrested were Lawrence Neumann, age 53, of McHenry, Ill., and Wayne Matecki, age 30, of Northridge, Ill. The six men were charged with burglary, conspiracy to commit burglary, attempted grand larceny, and possession of burglary tools. They were all lodged in the Clark County Jail.

When reporters asked how the lawmen happened to be in the area at the time of the burglary, Yablonsky and Clifford weren't very specific. They denied that the arrests were the result of an informant's tip. But they did admit being aware that Bertha's was scheduled to be hit on the Fourth of July. The story the reporters were given that night was not exactly true, though. And there had really been seven gang members present at Bertha's, not six.

What the reporters weren't told was that Sal Romano, an expert at disabling alarm systems, was working as a part of the HITWG's counter-surveillance team that night. Unbeknown to the rest of the crew, two agents from the FBI's Tucson office, Donn Sickles and Bill Christensen, had flipped Romano several months earlier. Based on information he provided, the lawmen knew virtually every detail of the gang's plan well before July Fourth. When the signal was broadcast to arrest the burglars, Romano was removed from the area and placed in the Witness Protection Program. His role in the Bertha's operation wasn't made public until several years later.

But the Outfit knew there had been a traitor, and they didn't like it. It wasn't Romano individually; it was that he, Weasel Fratiano, and others were becoming snitches. A pattern seemed to be developing that made Chicago nervous. Once-trusted members and associates were making deals to save their own skins. Honor among thieves seemed to be rapidly becoming a thing of the past.

The HITWG burglars after being arrested on July 4, 1981. From left: Ernie Davino, Lawrence Neumann, Wayne Matecki, Leo Guardino, Joe Blasko, and Frank Cullotta. (Courtesy Gene Smith)

Aftermath

Frank Cullotta was released from jail on bail following his arrest for the Bertha's burglary. But in November he was back in the slammer for a previous crime. In this case a woman's home had been burglarized and her furniture stolen. The missing items were subsequently found in Cullotta's residence, and in a grand jury indictment he was charged with possession of stolen property. Due to already being free on bond from the Bertha's arrest, the judge set a high bail. But the resourceful Cullotta was able to come up with the assets necessary to extricate himself from jail.

On April 20, 1982, Deputy D.A. Jim Erbeck won a jury conviction against Cullotta on the possession of stolen property charges from the previous November, and he was sent back to jail. But this time he faced the likelihood of being adjudicated a habitual criminal and a possible sentence of life in prison.

Although his present incarceration had nothing to do with Bertha's, Cullotta knew he was in big trouble over that case, too. The prosecutors had him and his fellow burglars nailed, with serious prison time only a forgone formality. But the law wasn't Cullotta's only worry. He had been in charge of the Bertha's gig and had bungled it badly. Why hadn't he detected Romano's treachery in time? Why hadn't the law's surveillance of Bertha's been spotted? Romano had turned rat, how reliable would Cullotta be if the law turned up the heat? Tony Spilotro and the Chicago bosses were no doubt asking those questions.

Metro liked Cullotta for the 1979 murder of a guy named Jerry Lisner, and attempted to interview him about that killing while he was locked up. He rebuffed them, but he knew what they wanted to talk about. The cops didn't give up easily and kept the pressure on. Even though he was keeping Metro at bay, having been around crime and criminals for most of his life, Frank Cullotta could sense when all was not well in his world. The fact that Spilotro was violating mob protocol by not returning phone calls or taking care of him and his family spoke volumes. He knew he was in jeopardy on all fronts.

The FBI soon arrived on the scene with new information that proved to be pivotal in the effort to attain Cullotta's cooperation. On the afternoon of Friday, April 30, Charlie Parsons had a job to do before beginning his weekend. He contacted Cullotta's lawyer — who also represented other organized crime figures — and asked to meet with him and his client at the jail. Parsons left his office at around 5 p.m. and drove to the meeting. He explained to his audience that he had obtained credible information that the Chicago Outfit had authorized a contract to have Cullotta killed.

"We had a policy that if we were aware that someone's life was in danger we had to inform that person, regardless of who he was or what we thought of him," Parsons explained. "I told them that it had been a long week and that I would be brief. I made my announcement and left. The threat was real, but my matter-of-fact delivery was intentional, and designed to get Cullotta thinking."

The strategy worked. Shortly after arriving at his office Monday morning, Parsons received a phone call. The caller said he was the man Parsons had talked with Friday afternoon. He wanted to meet again, this time without his lawyer. For Tony Spilotro, things were about to start unraveling.

Frank Cullotta wanted to live, and in return for that chance he was willing to talk. In just a few days, he had a new lawyer — one without mob connections — and an agreement with local and federal prosecutors. He would admit to various charges and serve a federal prison sentence determined by a judge, based on a recommendation from prosecutors. Any local charges that were not part of the plea arrangement would be dropped. After serving his sentence — which turned out to be seven years — he, his wife, and their daughter, would be placed in the Witness Protection Program. To get that deal, Cullotta had to cooperate fully and honestly with law enforcement, and testify in court proceedings as necessary.

Less that two weeks after Charlie Parsons had informed him of the contract on his life, Frank Cullotta was out of jail and his family was under law enforcement protection. Still technically in the custody of Clark County, he was housed in various hotel and motel rooms around Las Vegas. For security purposes, the longest stay in any one place was two nights. Debriefing began immediately, and was a joint effort by Metro and the FBI from the start.

"We worked hand-in-hand with the FBI," Gene Smith said. "Frank remained in our custody for about a month before we formally turned him over to the feds. Metro was responsible for his security during that stage and we knew the bad guys wanted him dead. I told my men, tongue in cheek, that if Cullotta got killed there had better be a number of dead cops around his body to keep it company."

In addition to hotel rooms, Cullotta spent some of his time as Metro's guest in a well-equipped motor home the cops had obtained during a drug bust. "Frank liked to fish and we took him out to Lake Mead for a couple of days so he could do some fishing. He really enjoyed that," Gene Smith recalled.

The lawmen treated Cullotta with respect, and a bond soon developed between them. "He called me Lt. Gene," Smith said. "He came to think of himself as part of the team. I remember he'd say to me in his Chicago accent, 'We're gonna get these guys, ain't we?'

During the Metro phase of his debriefing, Cullotta provided information that allowed the police to clear about 50 of their previously unsolved burglaries. He also admitted to the Lisner killing. But in order to get a murder conviction in Nevada, the law required that other evidence be presented to corroborate the suspect's confession. In the Lisner case, no such hard evidence could be found.

"We tried," Gene Smith said. "Frank took us out to where he said he threw away the murder weapon, but the gun wasn't there. It had been almost three years, though, so that didn't come as a big surprise."

As the case agent, Dennis Arnoldy worked the Cullotta debriefing with Metro from the beginning. He remained Cullotta's primary interrogator after the feds took custody of the informant. "Once we took control of Frank we got him out of Las Vegas. After that we only brought him back for legal proceedings. For Frank's protection we had to move him around regularly. I met with Frank hundreds of times during the following months in various locations across the country, including while he was in prison serving his sentence. Frank was treated courteously and our discussions were always civil in nature."

Cullotta Outed

"We tried to keep Cullotta's defection a secret," former Strike Force lawyer Stan Hunterton said. "We were doing okay until Frank provided information that one of the other Hole-in-the-Wall Gang burglars, Wayne Matecki, had fallen out of favor with Spilotro and was going to be killed by one of his colleagues. The alleged hit man was in jail, but was trying to get out on bail pending an appeal of his conviction. We contested the motion, of course. During the bail hearing, Charlie Parsons testified and had to divulge that the source of our information was Frank Cullotta. A gasp went up from the spectators in the courtroom. The word was out, generating a buzz in the media."

The hit man who Frank Cullotta said planned to kill Wayne Matecki was fellow HITWG burglar Lawrence Neumann. Neumann was a very dangerous man. He had been convicted of a triple murder in Chicago in 1956. In that incident he used a shotgun to kill the bartender, the bartender's brother, and a waitress in a Chicago tavern. The local papers reported that the slayings were the result of a dispute in which Neumann thought he had been short-changed in the amount of $2. He left the bar, returned with the shotgun and opened fire. He was sentenced to 125 years in prison. For all practical purposes that should have been the end of Mr. Neumann's criminal career. Incredibly, though, the killer was paroled in 1968, after serving only about 11 years of his prison term.

Stan Hunterton knew that as long as Neumann remained free he posed a threat to the public in general, and to potential witnesses in particular. He also knew that Frank Cullotta was providing information that would eventually put Neumann away for a long, long time. What Hunterton needed to do was get a conviction against Neumann that would keep him locked up until he could be prosecuted on the new charges. To accomplish that goal, he went after Neumann on a still unresolved 1981 charge of an ex-felon in possession of a concealed weapon. The gangster was convicted and sentenced to two years, the maximum sentence allowed at that time. It was during the appeal process from this conviction that Neumann was trying to attain bail so he could kill Matecki. Bail was denied, and Neumann was subsequently convicted of murder in 1983, and put away for good.

As more people became aware of the Cullotta situation, the concerns for his safety increased. "Frank was one of the best protected witnesses I ever dealt with," Hunterton added. "He had a lot of information we were interested in. He was a valuable asset and was treated as such."

Cullotta's Overall Effectiveness

Spilotro attorney Oscar Goodman later stated that Cullotta was a bust as a government witness. Dennis Arnoldy disagrees with that contention. In his opinion Cullotta was a very productive cooperating witness. The former agent believes you have to look beyond Bertha's to properly evaluate Cullotta's overall benefit to the government.

To support his argument, Arnoldy cites statistics of Cullotta's productivity between 1982 and 1988. In that time frame, Cullotta's testimony during various federal and state grand jury appearances and trials was instrumental in obtaining a number of indictments and convictions. There were 19 federal racketeering-related indictments; four Illinois murder indictments, and five Nevada burglary and armed robbery indictments. These charges resulted in 15 federal convictions, one Illinois murder conviction, and five Nevada burglary and armed robbery convictions.

In addition, Cullotta testified before the President's Commission on Organized Crime, the Florida Governor's Commission on Organized Crime, and at a sentencing hearing for Chicago mobster Joseph Lombardo.

The turning of Frank Cullotta impacted on many people in one way or another. To the law enforcement personnel who had made it happen, it made the endless hours of surveillance, interviewing, confrontations, and risk-taking all worthwhile. To many of their opponents it meant the beginning of the end. For Tony Spilotro, his former friend's move increased the already tremendous pressure he was under. But Tony was a tough guy, and he still had some fight left in him.

For more information about the author or to place a book order, please visit: http://www.authorsden.com/dennisngriffin.

The author is available to speak on police history or the Tony Spilotro era in Las Vegas. Email griff1945@hotmail.com.