Charles Ponzi

Charles Ponzi, a poor immigrant from Lugo, Italy, pulled off an amazing investment scam in 1920 that defrauded U.S. investors of $20 million ($240 million in today’s money). In the process, he perfected the infamous “Ponzi Scheme” that was taken to new heights by the likes of Bernie Madoff, Tom Petters and AllenStanford.

by Mark Pulham

Recently, on its website, Time Magazine listed its Top Ten Swindlers. They ranged from William Miller in 1899, to the recently convicted Allen Stanford in 2012. All 10 had something in common, apart from being crooks. They decided to steal their money by using a Ponzi scheme.

The Ponzi scheme has now become so common that, seemingly, hardly a month goes by without hearing an incident of another one. The financial pages are always reporting them, and those who run them become criminal superstars.

And we are not talking about amounts that run into the hundreds or thousands, or even hundreds of thousands. These are schemes that bring in millions, and sometimes, in the case of three on the list, billions. Tom Petters took in $3.65 billion; Allen Stanford $7 billion; and the man whose name is now synonymous with fiscal immorality, Bernie Madoff, between $50-$65 billion.

Surprisingly, there are still some people who don’t know what a Ponzi scheme is, or how it works.

A Ponzi scheme is amazingly simple to run. Except for some minor details, it is similar to a pyramid scheme.

It begins when a con man finds someone to invest with him. He will likely talk about financial matters, throwing around buzzwords such as hedge funds and high yield returns, and will present himself as someone very knowledgeable in financial matters and investment strategy. He may even hint that he has insiders giving him tips.

One thing he will do is guarantee that you, the investor, will make a larger than average profit on this investment within a short space of time.

The investor does not have to do anything other than sit back and wait for the money to start rolling in.

It sounds like a great deal. Almost too good to be true, which should be everyone’s first warning.

Let’s say the investor hands over $1,000 for a guaranteed return of 50 percent per month. At the end of the first month, the investor receives a statement showing that he has made $500. The investor can, if he wants, cash in and take his money, in which case the con man hands him $1,500. But $500 for doing nothing – that’s easy money. Chances are the investor will let the money ride for larger returns each month. And sure enough, each monthly statement shows an increase in profit.

What the investor does not know is that the con man is making no investments at all. The official looking statement has been created by the con man himself.

What the con man has done is recruited more investors into the same scheme, giving them the same promises and guarantees, and sending them the same fake statements. If he has recruited 10 new investors, that’s $10,000 added to the con man’s account. If the first investor wants to take out his profit, or cash out altogether, the con man simply takes the cash from the new investors’ money and pay him off.

To pay the second level of investors, the con man simply pays from a third level of investors, and so on. Each level can have the same number of investors, but generally, the con man would recruit at least double the number of the previous level, just in case that previous level all want to cash out at the same time, which is unlikely, but possible.

It helps the recruitment drive if the con man can point to the earlier investors and show that they made money on the investment, so word of mouth from previous investors bring in more people. As long as there are new investors that the con man can recruit, the plan will continue to be successful, and the profits for the con man can become astronomical.

But it is here that the scheme will begin to collapse. At some point, the con man is not going to be able to recruit new investors. If the con man is getting 10 new investors for every one in the previous level, then by the time he has reached the 10th level, he needs 10 billion investors to cover the last set, an impossible task as the population of the world is only seven billion. Even if he only doubles the number of investors for each level, he reaches beyond the population at level 34.

However, the scheme will collapse long before that point, though the more investors he persuades to roll over their investment, the longer the scheme can last.

There are differences between the Ponzi scheme and a pyramid scheme. One is that in the Ponzi scheme, the con man does all the recruiting, while the investor does nothing. This means that the investor, even if he was lucky and got out early with all his money and profit, is still technically a victim of the scheme.

In a pyramid scheme, the investor has to do the recruiting, and he knows that his profit comes from the new investor. He may be given something to sell, such as a start up kit, but he knows that he will not make any money unless he brings in new investors. The significance is that when the scheme collapses, which it will for the same reasons a Ponzi fails, the investor is not a victim but a collaborator as he knows where the money is coming from, and could also face jail time if prosecuted.

Another difference is that a Ponzi scheme is always illegal, whereas a pyramid scheme can be legitimate. Mary Kay cosmetics, Tupperware, the Pampered Chef, and Avon are all legitimate pyramid schemes, though they prefer the term Multi Level Marketing. The money is made not by bringing in new members, but by selling a product. If you bring in a new member, you may get a bonus, but that’s exactly what it is – a bonus.

So why is it called a “Ponzi” scheme?

|

| A young Charles Ponzi |

Although it was known by various names before, it was in the 1920’s that it began to be known as a Ponzi scheme, thanks to a charismatic Italian immigrant who was so successful at the scheme that it was renamed in his honor, or dishonor.

He was born Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi, the son of a postman, on March 3, 1882, in Lugo, Italy, though he himself would tell people that he was from Parma. His early life is mostly unknown, though Ponzi himself gave accounts of his youth. However, with Ponzi being a con man, it’s difficult to tell what is true, what is fabricated, or what is embellished.

Not long after his father died, Ponzi was accepted into the University of Rome - La Sapienza, much to the delight of his mother. But, far from home, he met up with some wealthy fellow students and, neglecting his studies, spent much of his time with them in bars and cafés.

The lifestyle of his new friends was one of lavish indulgences, and Ponzi went along with it, unable to afford the same lifestyle, and rapidly blowing through whatever inheritance he had got from his father. Ponzi began to skip classes, and slept the day away before getting up late and joining his friends for the extravagant nightlife.

It became clear to Ponzi that he was not going to get a degree, and it seemed he had no choice but to drop out of University. On the suggestion of an uncle, Ponzi decided to try his luck in the United States, considered to be the land of opportunity. His family bought him a ticket for the steamship and gave him $200, which would allow him to establish himself in America. He said goodbye to his family, and then headed for Naples, where, on November 3, 1903, he boarded the S.S.Vancouver that was headed for Boston, Massachusetts.

But Ponzi had not learned his lesson from life at the University. The ticket he had been given was for second class, and so he avoided the misery of steerage with its cramped and filthy sleeping quarters. With his inflated sense of self worth, Ponzi fell into the same habits that he exhibited in Rome at university, spending money on drinks and small luxuries that he could not afford, tipping waiters generously, and gambling.

It wasn’t long before the card sharks smelled blood and began circling. Ponzi was invited to join a “friendly” game of cards, and his $200 rapidly began to shrink. By the time the ship reached America, Ponzi was left with just $2.50.

The S.S. Vancouver docked in Boston Harbor on November 17, 1903, and, after satisfying the immigration officials, Ponzi stepped onto American soil. His family, no doubt seeing his behavior in Rome, must have known he would arrive in America virtually penniless, so they had also provided him with a prepaid train ticket to Pittsburgh, where he could stay with a relative.

For the next four years, Ponzi worked his way up and down the East Coast with a succession of menial jobs. He was a grocery clerk, he repaired sowing machines, and he sold insurance. But none of these jobs lasted very long. Some he was fired from, some he quit before he was fired. At one point, he was working in a restaurant, starting as a dishwasher, but working his way up to being a waiter. However, he was eventually caught short changing a customer and was fired for theft.

In those four years, Ponzi had changed. He had grown a moustache, become fluent in English, and had changed his first name from Carlo to the more Americanized Charles.

In July, 1907, Ponzi decided to move out of the United States and head north to Canada. He caught a train for Montreal and there wandered around, once again with hardly any money in his pocket. But that was about to change. Just a few blocks from the railway station Ponzi saw a bank, the Banco Zarossi.

Ponzi, confident as ever, walked through the doors and applied for a job, using the name Charles Bianchi. It took just five minutes, and he was hired as a clerk.

The bank had been founded by Luigi “Louis” Zarossi to service the needs of the Italian immigrants that were flooding into the city. Rival banks were investing the money in securities that were paying interest at a rate of 3 percent, passing on 2 percent on to their customers and keeping the other 1 percent as profit. Zarossi, to the annoyance of his competitors, was paying the full 3 percent, plus another 3 percent as a bonus. This was unheard of, and of course, people flocked to the Banco Zarossi for the 6 percent and his business grew rapidly.

The rival banks, fairly certain that there was no legal way Zarossi could pay that amount of interest, had their suspicions that he was paying his older customers with the money from his new customers, a process then known as “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” However, knowing something and proving it are two different things.

Months went by, and the Banco Zarossi flourished. But eventually, proving the rival banks correct in their assumptions, the Banco Zarossi found itself in financial trouble. By the middle of 1908, Zarossi, possibly on the advice of Ponzi, had fled to Mexico, taking with him whatever money was left in the bank.

Ponzi, unlike other members of the bank who had fled, stayed in Montreal, living with Zarossi’s family, who he had left behind. But, by August, Ponzi felt the need to move on, back to the United States. As usual, Ponzi had no money.

Ponzi’s First Two Arrests

On the morning of Saturday, August 29, 1908, Ponzi visited the offices of the Canadian Warehousing Company, a shipping agent that once had been a customer of the Banco Zarossi. As Ponzi had been there many times in the past, no one took any notice of him when he walked in. Ponzi crossed to the office of Damien Fournier, the company manager, and walked in. Finding nobody there, Ponzi quickly looked through the desk drawers, where he found a checkbook from the Bank of Hochelaga. Ponzi quickly tore out one of the checks and then left as swiftly as possible without causing suspicion.

Ponzi wrote out the check for the amount of $423.58, thinking this ordinary seeming amount would look more like a legitimate transaction, and signed it “D. Fournier.” True to his nature, the moment he had the cash, Ponzi began a spending spree, buying clothing and shoes, and a watch and chain.

|

| Ponzi jailed in Canada |

But the Bank of Hochelaga had become dubious, and had confirmed their suspicion regarding the check. Before he could even leave town, Detective John McCall had found and arrested Ponzi. Confronted, Ponzi immediately admitted that he was guilty. Charged and convicted of forgery, Ponzi was sentenced to three years in the Saint Vincent de Paul Penitentiary just a few miles from Montreal.

He started out breaking rocks, but soon, he used his skills to move himself into better positions, eventually becoming a clerk in the wardens’ office. He earned the warden’s trust and was a model prisoner, and his prison sentence was reduced to just 20 months for good behavior.

Just two weeks after he was released, Ponzi was on a train heading back to the United States. On the train with him were five other Italians. When a customs inspector boarded the train, he questioned Ponzi about the other Italians. Ponzi said that he didn’t know them, explaining that he had run into a friend at the station who asked him to accompany the men as they were unfamiliar with the country. He didn’t mention that this “friend” once worked at the Banco Zarossi where he had pocketed money from customers, and had fled after the collapse of the bank. Ponzi also never mentioned that money had exchanged hands.

The five Italians had no immigration papers, and Ponzi, before he had even crossed the border, was arrested for smuggling illegal immigrants into the United States. He received a two year sentence in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, Georgia.

Ponzi made a couple of new friends there. One was Mafia member Ignazio Lupo, known as “The Wolf,” a Black Hand leader in New York.

Once again, Ponzi worked in the warden’s office, and the warden asked Ponzi to translate Lupo’s letters, hoping to find something incriminating. Ponzi had no problem with this. He knew that nothing in the letters was incriminating, Ponzi shared a cell with Lupo, and he was writing Lupo’s letters for him.

The other friend he made at the prison was a much more interesting person, from Ponzi’s point of view.

Charles W. Morse was a wealthy and amoral Wall Street businessman, once known as the “Ice King” as his ice supply business had at one time held a virtual monopoly on New York. His monopoly ended when an investigation revealed the number of bribes he had made to politicians. However, by that time, he had managed to make a profit of $12,000,000.

After buying at least twelve banks, Morse tried to corner the copper market. The scheme failed and partially caused the financial panic of 1907. Morse was eventually convicted of the misappropriation of bank funds, and sentenced to Atlanta for 15 years.

But, in January, 1912, after serving only two years in prison, Morse was granted an unconditional release following an illness that left him perilously close to death. If he remained in prison, his lawyers argued, he would die. This was confirmed by doctors who examined him on a number of occasions. Morse was supported by wealthy financiers who appealed to President Taft.

Once Morse was freed from prison, his health rapidly improved. It turned out that just before he was due to be examined by doctors, Morse would swallow a mixture of shaved soap and chemicals, producing the symptoms of sickness. These symptoms lasted barely longer than the examination.

To Ponzi, Morse was fascinating, and Ponzi realized that the legal system treated the wealthy differently than it did the poor.

Ponzi, after he was released, moved south for a while, spending several months at a mining company in Blocton, Alabama, working as a translator and bookkeeper, but in 1917, he eventually made his way back to Boston, where his adventures in America began 14 years earlier.

Ponzi Falls in Love

On Memorial Day weekend, Ponzi was at a Boston Pops concert, accompanied by his landlady, when he spotted a beautiful young woman. It happened that his landlady knew her, and she introduced Ponzi to her. Her name was Rose Maria Gnecco, at 21 years of age, the youngest child of a fruit merchant. Ponzi immediately fell in love with her.

It was a whirlwind romance, and despite the revelations of his past in a letter to her from his mother, on February 4, 1918, Rose and Charles Ponzi married at St. Anthony’s Church on Vine Street.

Ponzi worked a variety of jobs for a period of time, including a job at his father-in–law’s business, but he wanted to strike out on his own, and rented some rooms on the fifth floor of 27 School Street. After a couple of attempted start ups, Ponzi came up with an ambitious plan. He would publish his own foreign trade magazine that would be a reference guide for businesses all over the world. His ambition was to double the circulation at regular intervals.

He would start out with 100,000 free copies that he would mail out to companies, and then, some time later, mail out an updated edition to the same companies, plus a free mailing of the magazine to 100,000 more companies. The advertising generated would make him rich.

Ponzi estimated that the initial mailing would cost $35,000, but the advertising for the first edition would bring in $80,000. The problem was acquiring the initial start up money, and he tried to entice investors into the business. None were interested, and Ponzi was running through his own money rapidly.

The guide didn’t even make it to its first edition.

But Ponzi wasn’t daunted by the failure of this enterprise. It was not the first time a business venture had fallen through and he knew that something else would turn up. And within a short while, something did.

It was August, 1919, and Ponzi was in his office going through his mail. One letter was from a business in Spain, asking about the now abandoned catalogue. For Ponzi, it wasn’t the letter that he found interesting; it was the square slip of paper that accompanied it, something Ponzi had never seen before. It was an International Reply Coupon.

The Ponzi Scheme is Born

The International Reply Coupon, or IRC, was introduced in April, 1906, at a Universal Postal Union congress held in Rome. Sixty-three countries, members of the Postal Union, gathered to make it easier to send mail internationally. Up until that time, it was extremely difficult to send anything between nationalities that required a return, stamped envelope. Foreign stamps could not be purchased in other countries, and if the stamps from the original sender were included, they would be turned away. If the sender included cash to pay for stamps at the other end, it required the person to go to a bank, exchange the foreign cash for the equivalent in his country, and then purchase stamps.

The International Reply Coupon eliminated all the problems. An IRC bought in Spain for the equivalent of five cents could be redeemed for a stamp of five cents in the United States.

But for Charles Ponzi, holding the slip of paper between his fingers, what he saw was not a solution to the return post problem, but a multi-million dollar opportunity.

Ponzi began to work out the figures.

The Great War had resulted in the devaluation of many world currencies, and Ponzi realized that the IRC had not been changed to reflect these devaluations. He knew that one of the worst hit currencies was the Italian lira. In the United States, one dollar could buy twenty IRC’s valued at five cents each. That same dollar in Italy could buy 66. He knew that if he purchased them in Italy for one dollar and then redeemed them in the United States for $3.30, his profit would be $2.30. All he needed to do was buy the coupons in bulk from foreign countries using American money, and then redeem them in the United States.

It was a process known as arbitrage, and it was not even illegal. Ponzi set up a new business and called it The Securities Exchange Company.

|

| Ponzi's house in Lexington, Mass |

As with his last venture, the first problem Ponzi had to solve was getting the initial amount of money to get the process moving. He went to friends and explained how the system worked, and some of them invested. Ponzi had promised them an unbelievable rate of interest. Within 45 days, he told them, they would make a 50 percent profit. He had a network of agents who would do the bulk purchasing in other countries and send the IRC’s back to Ponzi, who would then cash them in.

But there were other problems, ones which he had not told his investors. First, he didn’t have a network of agents buying up the IRC’s. Second, even if he did, the cost of shipping them to Ponzi in the United States would be incredibly high, possibly enough to eliminate the profit. And there was a third problem. He was informed by the postal service that they would not redeem the IRC’s for cash, but only for stamps. This meant there was the added problem of then selling the stamps as well.

But by this time, Ponzi was committed to this venture. He had promised returns, and he paid returns. Ponzi paid off the early investors from the money collected from the newer investors, and word of how much money could be made by investing with the Securities Exchange Company spread rapidly. Ponzi had started an avalanche.

Potential investors flocked to School Street to invest in the IRC scheme, and by February, 1920, Ponzi’s profit was $5,000, and by the following month, it was $30,000. By May, it was up to $420,000, the equivalent of over $5 million in today’s money.

By the middle of the year, Ponzi had made millions, with estimates suggesting that he was making around $1 million a week. By this time, he had purchased a controlling interest in the Hanover Trust Bank, which must have been satisfying as they had originally refused him a loan.

With almost everyone rolling over their money to be reinvested, the scheme ran on longer, but some people were already beginning to have some doubts about the business and questions were being asked.

One financial writer questioned the business, suggesting that Ponzi could never legally deliver returns this high in such a short period of time. Ponzi sued for libel, and as the burden of proof in those days lay with the writer, Ponzi won, receiving $500,000 in damages.

The Bubble Bursts – Investors Lose $20 million, Ponzi Goes to Prison

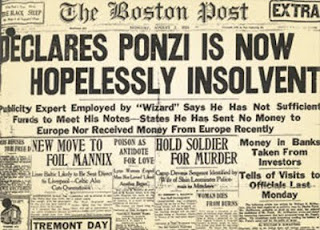

However, some time later, the Boston Post, which had run favorable stories on Ponzi and his business in the past, contacted financial analyst Clarence W. Barron, founder of financial journal, Barron's Magazine, to examine Ponzi’s claims. One of the things Barron noticed, other than Ponzi was not investing in his own business, was that to make the business work, there needed to be at least 160 million IRC’s in circulation. The problem was there were only 27,000.

|

| Boston Post |

The Boston Post printed the findings and this caused a run on Ponzi’s business, forcing him to pay out $2 million over a three-day period.

By this time, Ponzi had attracted the attention of Daniel Gallagher, the U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts, and he commissioned an audit of the Securities Exchange Company, which was made difficult by the fact that Ponzi didn’t keep any books on the business, just a stack of index cards and names.

Ponzi hired a publicity agent named William McMasters, but McMasters, having discovered what Ponzi was doing, instead wrote an article for the Boston Post claiming that Ponzi was at least $2 million in debt.

This was the beginning of Ponzi’s downfall.

Joseph Allen, the Massachusetts Bank Commissioner, worried that the run on Ponzi’s business generated by the story would bring the Boston bank system down. Bank examiners informed Allen that Ponzi’s main account was now overdrawn due to investors cashing out. Allen ordered the bank account to be frozen.

The Massachusetts State Attorney General issued a statement revealing that there was no evidence to support the claims made by Ponzi, and officials asked investors to give their names and addresses so that an investigation could be carried out.

That same day, the audit commissioned by Gallagher gave Ponzi a report of its finding. Ponzi’s debts were not $2 million, as claimed by McMasters. His debt was over $7 million.

The Hanover Trust Bank was seized by authorities, and five other banks were brought down by the scandal. Ponzi was fully aware that he was about to be arrested and so surrendered to the authorities, who charged him with mail fraud. His investors lost virtually everything, losing around $20 million, or almost $240 million in today’s money.

Ponzi was charged with 86 counts of mail fraud, which would have jailed him for the rest of his life. However, his wife, Rose, urged him to make a deal and plead guilty, which he did on November 1, 1920, on just one count. Ponzi was sentenced to five years in Federal prison.

After serving three and a half years, Ponzi was released, and immediately arrested once more and put on trial for 22 charges of larceny by the Massachusetts State. Ponzi was stunned. He believed that the deal he had made to plead guilty would result in the State charges being dropped. Although he sued, it was ruled that a plea bargain on Federal charges have no standing in regard to State charges.

The 22 charges were split into three trials. In the first, Ponzi was found not guilty on 10 of the charges. In the second, the result was a deadlocked jury on five charges. But in the third trial for the remainder of the charges, Ponzi was found guilty. He received a sentence of five to seven years. And, as Ponzi had not obtained citizenship, the authorities also wanted him deported at the end of his sentence.

Ponzi was released on bail as he appealed the State conviction, and immediately ran away to Florida, where, in September, 1925, he created an association, the Charpon Land Syndicate, offering investors land and promising returns of 200 percent in two months. But the land was actually swampland in Columbia County. In February, 1926, Ponzi was arrested and found guilty of violating the Florida Trust laws, and was sentenced to a year in jail. He appealed the sentence and paid a $1,500 bond.

Once out of jail, he fled to Tampa, where he shaved his head and tried to flee the country on a ship heading for Italy. However, the ship made one last call in New Orleans and he was recognized and captured, and sent back to Massachusetts where he served seven more years in prison.

Ponzi Deported

In 1934, upon his release, Charles Ponzi was deported back to Italy.

|

| An older Ponzi |

Rose, the love of his life, didn’t want to leave Boston, and so she stayed behind, and finally divorced him in 1937. Rose later remarried and became the bookkeeper for the New Cocoanut Grove nightclub.

Ponzi tried more schemes while in Italy, but each of them failed. Eventually, he began working for Ala Littoria, Italy’s state airline, and moved to Brazil to be their agent there. However, when Brazil sided with the allies during World War II, the airlines operation in Brazil was closed down.

Ponzi worked as a translator for a while, but his health was now failing. In 1941, Ponzi, now 59 years old, suffered a heart attack which left him very weak. By 1948, his health had severely deteriorated. He was almost blind, and had suffered a brain hemorrhage that had left him paralyzed down his right side.

On January 18, 1949, at the Hospital São Francisco de Assis, at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Charles Ponzi died. He was 66 years old. The man who had made millions passed away in a charity hospital, penniless, and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Some believed that Ponzi never intended to rob people, and that he truly believed the IRC business would work. But the business was flawed and before Ponzi could stop it, the business snowballed. It’s possible, though unlikely.

But whatever the truth about Ponzi, his name has entered the English language, and is almost never said without the word “scheme” spoken straight after.