Updated Nov. 7, 2011 and June 22, 2014

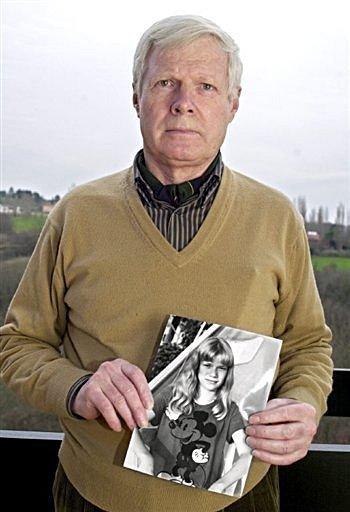

André Bamberski

For 27 years the heartbroken André Bamberski kept an eye on the fugitive serial rapist who murdered his 14-year-old daughter. Then he arranged a vigilante kidnapping to deliver the murderer to the police.

In the early hours of the morning little happens in the town of Mulhouse.

Mulhouse, of slightly over 110,000 inhabitants, is geographically in eastern France, in the region of Alsace, but it is often said by skeptical French that the Mulhousiens and the Mulhousiennes, as the inhabitants are called, have German hearts. The reason is that Germany starts just a few miles east of Alsace, and indeed of Mulhouse, and the Germans have therefore annexed the region three times. The first annexation had been after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian war (July 1870-May1871), the second, during World War 1 (1914-1918), and the third in World War Two, after France’s June 1940 capitulation to Adolf Hitler’s Nazi army. This third annexation had lasted until the end of the war in May 1945. Since, Alsace has remained French.

During the early morning of Sunday, October 18, 2009 Mulhouse was again silent, but the silence was disturbed when the computer screens in front of the officers on duty in the police’s emergency call room flashed an incoming call.

The caller, a male, speaking with a marked Russian accent despite his flawless French, gave the cop who took the call the name of a local street: Rue de Tilleul. On that street, said the caller before he rang off, the fugitive, Dieter Krombach, could be found.

All calls to the police’s nationwide emergency number – 17 – are recorded, so, having the correct spelling of such a foreign name, it did not take the Mulhouse police long to verify whether a man named Dieter Krombach was on the run from French justice.

Dr. Dieter Crombach

He indeed was.

A German national and a cardiologist, he was convicted in a Paris court in 1995 of the manslaughter of a 14-year-old French girl, Kalinka Bamberski. He had been sentenced to 15 years, but as the crime had been committed in Germany where the cardiologist was domiciled, the Germans had refused to extradite him to France and the sentence had been passed in absentia.

Knowing who Dieter Krombach was, a squad car sped off to Rue Tilleul, more a short, narrow lane than a street, and only four blocks from police headquarters.

And yes, the fugitive was there. Dressed in dark pants and anorak, securely trussed with thick rope and gagged with cloth and tape, he lay in a fetal position close to an iron gate at the entrance of the lane. His thin, gray hair was speckled with blood; he had several bleeding gashes to his head and face. Asked his name, he said in the nasal voice of a German speaking French that he was a German national. He wanted to know where he was; he said that he had been kidnapped from his home in Lindau, Germany. Told that he was in France, in the border town of Mulhouse, he demanded that he be untied and released instantly so that he could go and clean himself up in a hotel.

The police obliged.

They drove Dr. Dieter Krombach to a hotel: The hôtel de police – police headquarters.

Under French law, the moment he had confirmed his identity to the police, he had admitted that he was the convicted murderer Dieter Krombach who had been on the run from French justice since 1995, and he was automatically under arrest.

He was told that whatever he would say from that moment on could be used as evidence against him.

He said that he was not feeling well, that he was having a heart attack. As a cardiologist, he said, he recognized the pain in his chest as a heart attack.

The squad car continued on to police headquarters.

What was it all about?

The story goes back 27 years to the summer of 1982.

It was Friday, July 9, and a hot day was ending when the 14-year-old Kalinka Bamberski returned home from a day of wind surfing. Home was a comfortable villa in the town of Lindau on Lake Constance. The lake, 40 miles long and nine miles wide, is shared by three countries – Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Lindau with its 25,000 inhabitants falls in that sector of the lake that is Germany.

Kalinka Bamberski

First thing that Kalinka did on getting back home that Friday evening was to look at herself in the mirror to see whether she had tanned that day. She was a blonde, blue-eyed and very fair-skinned girl, and a tanned skin was all the rage. She had therefore made up her mind, when she started her new school that coming September, she wanted to be golden brown. Her new school would be in France, in the village of Pechbusque (Pop. 800) close to the southwestern town of Toulouse where her father lived. The house in Lindau was where her mother lived; her mother, Danièle, and her step-father, Dieter Krombach, and her biological brother Nicolas, and her two older step siblings, Boris and Diana.

Kalinka’s family history was somewhat complicated.

She was born in 1967 in Casablanca, Morocco, of the French Danièle and a Polish-born but naturalized-French father, André Bamberski. In World War II, André, then only 3 years old, had been deported with his parents from Poland by the Germans to a concentration camp in Germany, but the family had miraculously survived and had, after the war, settled in northern France where Bamberski Sr. had worked as a coal miner. The adult André, good with mathematics, had become an accountant, and after his marriage to Danièle the couple had set off for Morocco. When their first child – Kalinka – was born, they named her after a flower that grows in the forests on the banks of the Polish lake of Mazurie. In 1976, the couple, by then parents to a second child, Nicolas, returned to France and settled down in Pechbusque. In Pechbusque they befriended a German cardiologist – Dieter Krombach – who lived five houses down the road. He was a widower and father of two children, Boris and Diana, both a little older than the Bamberski children. It was not long before Danièle left André and their two children to accompany Krombach and his two children to Germany.

So in love with Krombach was Danièle that, as André would tell journalists later, she had not objected when he filed for divorce and the court gave him custody of Kalinka and Nicolas.

Her love might even have been so intense (only she knows) for her new husband that she had not asked him about the death of his first wife. The first Mrs. Krombach had died under suspicious circumstances: Only 24 years old, she had collapsed after Krombach had given her an injection. In the compulsory inquest that had followed the woman’s death, the police had found no reason to believe that foul play had been involved.

In 1980, Danièle Krombach, by all appearance in a stable and loving marriage, had returned with success to a French court to have the custody of Kalinka, then 12, and Nicolas then 7, transferred to her. She, however, sent Kalinka to a boarding school close to Lindau. Therefore, in July 1982, the girl was at the Lindau villa for the summer school vacation. But, unhappy at the boarding school, she was not going to return to it; she had persuaded her mother to allow her to return to live with her father in France, there where she was happiest, and this return to her father and France was scheduled for the start of the new school term that coming September.

First, however, Kalinka wanted to get a tan.

Her stepfather said that he could help her to tan faster. He would inject her with a substance.

Or, this was the story he told doctors and police, because Kalinka Krombach did not survive whatever he had injected her with.

Kalinka’s death.

The events of the 48 hours that followed the evening of July 9, 1982 when Kalinka returned from a day of wind surfing, are confusing, each of those who were present in the Lindau villa, telling a different story.

But at 9 a.m. on Saturday, July 10, Kalinka was dead in her bed.

According to what Krombach told a colleague, Dr. Jobst of Lindau hospital’s ER, whom he summoned to the villa that morning, he had injected Kalinka at around 7:30 the previous evening with a substance to help her tan. He had given her the injection before dinner when she was sitting on a chair in the living room and her mother was present. He did not name the substance. Later that evening, at around 10:30, as his story continued, he had looked in on her in her bedroom and had given her a glass of water because she told him that she was thirsty. He did not explain why he had felt it necessary to look in on her. At midnight he had returned to her bedroom because her light was still on and he wanted her to switch it off and to go to sleep. She told him that she was not sleepy. He had therefore given her a sleeping tablet to drink. In the morning, he had found her dead in her bed. Again, he had not given a reason for having gone into the girl’s bedroom that morning.

Dr. Jobst, who was accompanied by an assistant from the hospital, had arrived at the villa between 9 and 9:30 that morning. They took a cardio-electrogram reading of the lifeless Kalinka’s heart and at 10:30 the doctor declared her dead. He issued a death certificate. Not stipulating a cause of death (in both France and Germany the cause of death is not given on a death certificate) he transported the girl’s body in his ambulance to the hospital’s morgue. An autopsy was to be performed.

The autopsy was carried out on the afternoon of Monday, July 12, some 45 miles away at the hospital in the town of Memmingen. The two autopsy surgeons, the Drs. Höhmann and Dohmann, performed the autopsy in the presence of a prosecutor, a man named Schnabl based at the court in Kempten (the region’s capital town). Present also was a Lindau police commissioner, a certain Gebath. There was also someone else standing at the autopsy table, watching the proceedings: Dr. Dieter Krombach.

The autopsy report, first dictated and then typed out was 16 pages long.

The Drs. Höhmann and Dohmann stated as follows:

(1) Kalinka’s body was already in a state of advanced decomposition.

(2)There was a bloody intravenous injection mark on her right upper arm.

(3)There were two dry injection marks on her body. One was on her thorax and the other on her right leg.

(4)There was undigested food in her stomach as well as in her esophagus and in her lungs (the alveoli of her lungs).

(5)There was fresh blood on both the large and small lips (the labia majora and the labia minora) of her vulva (external genital organ).

(6)The right lip of the vulva was torn and very bloody.

(7)There was a white substance present in the vagina (internal genital organ).

The two offered no explanation for the state of the girl’s sexual organs other than that the tear in the one lip of the vulva had happened before death. They did not go into what the white substance in the vagina was or could have been. Or whether she was a virgin, and when she had had her last period. And although there was food in her stomach, esophagus and the lungs which showed that choking could have caused her death, the two stated that Kalinka had probably died of heart failure. They also did not offer an explanation for the already advanced state of decomposition of her body.

They put the time of her death at between three and four on Saturday morning despite that the food in her stomach, esophagus and lungs were still undigested; as she had eaten her dinner at around 7 p.m. on July 9, the food would already have been digested eight or nine hours later. In other words, at 3-4 a.m. on Saturday.

Krombach would not be questioned by the police about the events of that previous Friday night and Saturday morning until the next day. And the questioning was done in a telephone call from Commissioner Gebath.

What Krombach in that call told the commissioner differed from what he had told Dr. Jobst from Lindau hospital’s ER.

He said that Kalinka suffered from anemia and was always tired so he had given her an injection for anemia in the presence of her mother, and this he had done after the family had had dinner. He had, he said, intravenously injected her with Cobalt-Ferrlecit. This is an iron and cobalt medication for iron deficiency anemia. It also used to be administered by dermatologists and beauticians to people who wanted to enhance their skin color to look tanned, but this is a practice which has been (so it is being claimed) discontinued now because it is risky.

He added that at midnight, because she was unable to sleep, he had given her a Frisium™ tablet. Frisium™ is a sedative and muscle-relaxant and usually prescribed to people with severe anxiety or people suffering from epilepsy. It should not be taken over a long period as it impairs concentration and alertness, and can cause nightmares and hallucinations.

He continued that in the morning finding Kalinka inanimate in bed, he had injected her with Dopamine™ and Dilaudid™. The first is a neurotransmitter that increases the heart rate and the blood pressure, and the second is an analgesic and considered a narcotic.

No further questions were asked of Krombach. The other members of the family were not questioned at all.

André Bamberski learned of his daughter’s death at 11 o’clock on the Saturday morning in a telephone call from Danièle.

Since the breakup of the couple’s marriage, the two had had little contact, and on those occasions when they did, they had discussed the two children they had had together. They talked about with which one of the two of them Kalinka and Nicolas would spend the school vacations or Christmas, or Easter. That sort of thing.

But this telephone call on that Saturday morning was unlike all the others because they were speaking of their daughter’s death.

André was devastated yet also angry.

Hardly able to speak because of the chagrin he felt, he wanted to know from Daniéle what had happened. She told him that no one as yet knew, but that an autopsy would have to be held. She knew a little about such tings as compulsory autopsies after a sudden and inexplicable death because she helped out at her husband’s surgery and often had to advise the relatives of a deceased about an autopsy. She also knew that the police did not release a body until after they have the results of an autopsy and that it could take days, weeks even, for this to happen.

André, as he told his ex-wife, wanted their daughter to be buried in Pechbusque’s cemetery.

Pechbusque is a village of small salmon-pink, orange-tiled houses on narrow, steep streets. The village is ten miles from the southwestern French industrial city of Toulouse and close to the Spanish border. Paris is some 450 miles away. Lindau is more than 700 miles away and for André his daughter’s grave could not be so far from the house where his little family had lived since they had returned to France from Morocco.

He was going to buy a plot in the cemetery for a family tomb because one day he wanted to be buried with her. This was not an unusual wish because it is the custom in France for members of a family to be buried together in a little house-like tomb: parents, grandparents, children and grandchildren all lying together in death.

Danièle agreed with André that their daughter would be buried in Pechbusque, but on Tuesday, July 13, she was back on the phone to him. She wanted to know why he had told Prosecutor Schnabl that he wanted their daughter’s body cremated. This was what Commissiner Gebath had told her. André assured her that he had not given the prosecutor permission to cremate their daughter’s body and arrangements for the cremation were stopped. Later, speaking to journalists, André would say that if Kalinka’s body had been cremated then he would have had no evidence that she had been murdered.

Schnabl, also claiming that he was acting on behalf of André, next gave instructions to Commissioner Gebath that no further examination of Kalinka’s body or any analysis of tissues which might had been removed from her body ought to be done.

André would later tell journalists that Prosecutor Schnabl had given such instructions because he wanted to help Krombach escape prosecution, that it was one German looking out for another.

Schnabl was yet to issue another instruction. On Tuesday, August 17, six weeks after Kalinka’s death, he told Commissioner Gebath to stop the investigation altogether. Next, the inquest was held and it was ruled that no foul play had been involved with the girl’s death. The court did not however give a cause of death.

Kalinka’s body could be released for burial.

On the day of her funeral in Pechgusque, André Bamberski stood at his daughter’s grave and pledged to her that he would not let her murderer escape justice. He was certain that she had not died a natural death. There were, in his opinion, too many questions about her death to which no one had given him answers.

Danièle did not agree with her ex-husband. She believed that their daughter’s death had been of natural causes; tragically, the 14-year-old had died of heart failure.

On Wednesday, September 22, 10 weeks having passed since Kalinka’s death, André received the autopsy report. It was in German and unable to understand the language, he needed to have it translated. He received the translation 16 days later, on October 8, and then, having read the report, he had no further doubt that Kalinka had been murdered. Murdered by her step-father, Dr. Dieter Krombach. He believed that Krombach had injected her to put her to sleep and that he had then raped her.

A week later, André wrote to Prosecutor Schnabl to request that another analysis should be made of whatever tissues had been removed from his daughter’s body during the autopsy and which were still in the police’s possession. Schnabl waited seven days before replying to the letter: He wrote that there was no sufficient reason for a re-analysis of the tissues.

On Thursday, November 11, André hired a lawyer, Rolf Bossi, from the German city of Munich. The latter wrote to Prosecutor Schnabl to draw his attention to all the questions about Kalinka’s death for which no answer had been given. He also asked that the tissues be re-analyzed, and he wanted to be told the names of the injections that Krombach had given Kalinka.

In response to Bossi’s letter, Schnabl asked the Munich Medico-Legal Institute to re-analyze the tissues.

Three autopsy surgeons, the Drs. Spann, Drasch and Eisenmenger, did so.

In their report they confirmed that Kalinka had received an intravenous injection of Cobalt-Ferrlecit which had caused a not insignificant bleeding. They doubted that the injection had been administered immediately before or after she had had dinner; if so, the time between the application of the injection and her death – three or four o’clock of the following morning – should have been shorter. They also doubted that the injection had caused her death, but they ruled out that she had choked to death on regurgitating food. This conclusion they did not clarify. The cause of death they also did not stipulate.

On the state of Kalinka’s vulva and vagina, the three did not comment.

Bossi, not satisfied, asked Prosecutor Schnabl again for clarification with regards to the sexual organs. In reply he received a letter from Dr. Höhmann, who was one of the three surgeons who had carried out the initial autopsy. He wrote that he had nothing to add to the autopsy report.

Bossi had also asked Schnabl whether Kalinka’s sexual organs (external and internal) had been removed during the autopsy for a more in-depth analysis, but Höhmann, in his reply on behalf of Schnabl had ignored the question.

The year 1982 ended.

Early in 1983, asked by Bossi to do so, Commissioner Gebath questioned Danièle, Boris and Diana for the very first time.

On Wednesday, May 18, 1983, Danièle told the commissioner that she had not been present when her husband had injected Kalinka for her anemia which she knew he had done after dinner. She then contradicted herself by describing the girl as having been in good health. She said that her husband had woken her up “before 9” that Saturday to tell her that Kalinka was dead. She knew nothing more about her daughter’s death, she said.

Boris told the commissioner that he could not remember much about that Friday or Saturday, but that Kalinka did complain that she was not tanning as fast as she wished.

Diana told the commissioner that she also could not remember much about those two days. But she did remember that she was out until around midnight that Friday and on her return her father had stepped from the toilet on the ground floor of their villa and the two of them had chatted for a while. She had then gone to Kalinka’s room to fetch the family’s little dog which was sleeping on Kalinka’s bed. She had not looked at her half-sister to see whether she was asleep; she presumed that she was, because why would she not have been. She had learned that Kalinka had died during the night when Nicolas had woken her up on Saturday morning to tell her that her father was downstairs and wanted to talk to her. Her father had then told her that Kalinka was dead.

Nicholas, back living with his father in Pechbusque, was questioned only four months later, on Sunday, September 4, by the French police. He told them that Kalinka had been in “very good” health and that there had been nothing wrong with her that Friday, not during the day, nor that evening. He had, he said, spent the evening with her in the living room until she had gone to bed; he could not remember at what time that had been. He was adamant that his stepfather had not that Friday night given his sister an injection, not to tan or for any other reason, although the doctor had been giving her injections to tan for at least two years. He said that on the Saturday morning he was awakened by the siren of an ambulance which had pulled up outside the villa, and so he had come to learn that his sister had died during the night.

When Bossi received the four’s testimony, he, on behalf of André, asked Prosecutor Schnabl to reopen the case. The response was a letter from Kempten’s chief prosecutor, a man named Reichart, to inform him that there was not sufficient evidence against Krombach to reopen the case.

Desperate at the Germans’ lack of cooperation, André set off for Lindau. Once there, he started to hand out tracts in which he denounced Krombach as a rapist and murderer. As a result, Krombach, furious – and supported by Danièle – sued André for defamation of character. He won the case and André had to pay him half a million German Marks (about $200,000) in compensation.

But André would not surrender.

Two years went by.

In those years André had continued to distribute tracts in Lindau. He had spoken to the media of both Germany and France. He had appealed to French and German politicians to take up his case. He had started a support group, Justice for Kalinka, and had 300 followers.

In the course of 1985, three and a half years after Kalinka’s death, André, having yet again asked the Germans for clarification with regards to the autopsy, learned that her sexual organs had been removed during the autopsy. He asked for a re-analysis of these. He was told that this would not be possible; the sexual organs had been returned to France with the body. Now, he wanted the body to be exhumed, but a French court would not authorize this without a formal exhumation request from the Germans.

In December of that year the Kempten court finally sent a request for an exhumation of Kalinka’s body. The sexual organs were not in the coffin. Where were they? No one knew. André however believed that Dr. Höhmann had destroyed these to hide the fact that Kalinka had been raped. Raped by his colleague and pal Krombach.

The Germans still would not reopen the case.

A pledge is a pledge

The years passed. André Bamberski gew older. He was 30 years old when Kalinka was born and 44 when she died. Krombach was 46 when Kalinka had succumbed in his villa. Both men were by now in their sixties.

In 1995, finally, André succeeded in getting the French police to indict Krombach for the murder of Kalinka on the evidence that he had handed them; the anomalies in the autopsy report, the missing sexual organs, and the different stories told by those who had been present in the Lindau villa on the night of Kalinka’s death.

Krombach was to be judged in the High Court at the Palais de Justice in Paris. France requested Krombach’s extradition from the Germans, but they refused to hand him over; they said that they had investigated Kalinka’s death and had found no evidence that the doctor had raped and murdered her.

The trial was held anyway and Krombach was sentenced in absentia to 15 years incarceration for manslaughter. The French court had not been able to establish that he had raped Kalinka, but ruled that she had died as a result of the injections he had given her. Danièle had given evidence in support of Krombach, but theirs was a marriage that would soon end.

Krombach having been judged and convicted, but a fugitive, André began to focus on having him extradited.

By then many Germans, former female patients of Krombach had contacted André to share their suspicions with him that the doctor had raped them after he had injected them with a sleeping drug. There were times when it was not the patient herself who contacted him, but one of her relatives; the patient was still too traumatized to speak of the experience.

Another two years went by. It was 1997. The French State had made no effort to request Krombach’s extradition from Germany which André thought was because the French did not want to upset the Germans, the two nations having made it up after the terrible years of World War II when the Nazis had occupied the defeated France. The Germans, on their part, had also made no effort to arrest the doctor and to extradite him which André thought was because they were aware of France’s wish not to rock their boat of friendship.

Whether André was right or not, the reason for Krombach remaining a free man was not because the French and Germans did not know his whereabouts. They knew. André had told them. Krombach had moved house numerous times, but each time André had immediately known the new address; his supporters, the women who suspected that Krombach had raped them, had been keeping an eye on him for André. And André had even himself gone to Germany three or four times a year to verify the doctor’s address. He had even rung his doorbell and when Krombach had opened he had told him that he was going to get him.

That year of 1997, the Germans finally became interested in Krombach. The parents of a 16-year-old girl accused him of having raped their daughter after he had injected the girl, a patient of his, with a sleeping drug. Despite that another five patients gave evidence that he had also drugged and raped them, Krombach was given only a two-year suspended sentence. But his license to practice medicine was withdrawn for life.

Now for the first time, France asked Interpol to issue an international arrest warrant for Krombach, but Germany still refused to extradite him. So secure did this make Krombach feel that in 2001 he brought a case against France at the European Court of Human Rights based in Strasbourg, France, for having wrongfully indicted him for the rape and manslaughter of Kalinka. He won his case; the court ruled that France had denied him a fair hearing. The French State had to pay him 100,000 Francs ($23,000) in damages.

Undeterred, André and his supporters continued to watch Krombach.

In 2006, a German woman living in the German town of Coburg sent André word that Krombach was practicing medicine in the town. She had visited her cardiologist, a Dr. Grosse and had learned that he had committed suicide but that his practice had been taken over by another cardiologist – Dr. Dieter Krombach.

André told the German police and on Monday, November 20 of that year the Germans arrested Krombach and locked him up. In the trial that followed he was defended by the prominent Munich-based lawyer Steffen Ufer. Bizarrely, Ufer used to be the partner of Rolf Bossi, who had represented André in 1982. Ufer was therefore fully aware of Krombach’s history.

Krombach was sentenced to two years and four months for practicing medicine illegally and defrauding the state’s health system (without a license he could not register his fees with the authorities). The lifelong ban on practicing medicine was confirmed. One of the character witnesses called by lawyer Ufer was the woman who was at that time Krombach’s lover. She was 35 years his junior and before she had taken up with him she had been the lover of Dr. Gross, the cardiologist whose practice Krombach had taken over. In the inquest that had followed Dr. Gross’s death his family and patients had testified that he had not given them the impression of having been depressed or suicidal. The court had ruled however that no foul play had been involved in his death.

Grombach served a few months of his sentence and was released for good behavior; he returned to Lake Constance. A man alone, he changed address a few more times, and then he rented a modest apartment of two rooms in a house on a quiet street in the village of Schneidegg, on the edge of a wood close to Lindau. He seemed to enjoy his retirement, taking no notice of the suspicious looks his neighbors gave him; they knew who he was.

In April of 2009, the High Court in the German town of Munich rejected Interpol’s international arrest warrant. Krombach was free. At least, free until he set foot on French soil. That was something he was however unlikely to do.

André Bamberski strikes

Blood lying on the street in the village where Krombach lived was odd.

It was going on for midnight on Saturday, October 9, when one of the street’s residents on walking his dog, saw a pool of blood on the road beside a parked car. The car he recognized as that one of his neighbor – Krombach. Walking over to the car, he stumbled over a man’s shoe; close to it lay a truncheon. He summoned the police. They arrived and looked at the stain on the road and said that it was indeed blood. There was blood on the truncheon too. They knocked at the door of Krombach’s apartment. There was no reply. They then closed off that section of the street and sealed Krombach’s front door leaving a note for him to call the police on his return.

Krombach did not call the Lindau police, but the following morning the Mulhouse police did. They told their German colleagues that they had Krombach down in their cells.

By that time the Mulhouse police were already looking for André. He was not at home in Pechbusque and the day passed before his cell phone operator traced him to Mulhouse, and not that long afterwards to a hotel in the town. He was not surprised when the police knocked at his bedroom door.

André fully cooperated with the police. He did not kidnap Krombach personally, no, he said, but he had him brought to France. No, he had not seen him, he had only been told by the kidnappers where they’d left him. And, yes, he was the one who had called the police to tell them where they could find Krombach. And yes, he had disguised his voice in order to keep the police off his track for a while so that he could get to Mulhouse from Pecbusque. He wanted to be in Mulhouse to make sure that the police did not let Krombach go.

The police found €19,000 ($28,000 ) in notes in the room and André did not hide the fact that that was money that he was going to hand over to the kidnappers. Their names he said he did not know; he had not met them. Or maybe he had met one of them. He said that on Friday, October 9, 2009, while in the Austrian town of Bregenz (it is on Lake Constance’s too), he had been called down to the lobby of the hotel where he was staying. A man, who identified himself as “Anton”, was waiting for him in the lobby. The two of them had gone for a drive in Anton’s car and during the drive the latter had told him that he had read about Kalinka on the Internet. Later, speaking of this meeting in an interview with the French weekly Le Figaro Magazine, André would say:“He (Anton) told me: ‘I saw about your daughter on the Internet on the site Justice for Kalinka. A stop must be put to Krombach’s impunity. Will you agree to me bringing him to France?’ I replied that I would be. At no time did he ask me for money. I was the one who insisted on paying his expenses. He (Anton) accepted my offer with the words, ‘Okay, but no other information must you ask me.’” The two of them had spoken in English and Anton had spoken the language with a marked German accent.

As André would also tell the magazine, it was not the first time that such an offer had been made to him.

He said: “I had even twice accepted to meet the persons who had offered me to kidnap Krombach. The first time I had handed over 50,000 Francs ($11,000) and I never heard another word from the individual. The second time, I handed over 75,000 Francs ($17,000) and the crook also disappeared. It shows how desperate I was. If French justice had done its work I would never have had to even think of doing something like this. Some individuals had even proposed to me that they bump him of. Naturally, I did not go along with that.”

He also told the magazine that he had received a telephone call at around 10 p.m. on October 17, the night before the kidnapping, and the caller, a man disguising his voice to sound like a woman, had told him that he must prepare to set off for Mulhouse. At 3:30 a.m. the phone had again rung and the same voice had told him that Krombach was to be found on Rue du Tilleul; the caller had spelled out the name of the street to make sure he took it down correctly. It was then that he had made his call to the police. First thing in the morning he had flown to Mulhouse via Paris. However, before he could hand over the money to the kidnapper or kidnappers, the police were on the corridor outside his hotel bedroom and knocking at his door.

André Bamberski

The police indicted André for the vigilante kidnapping of Krombach. He was held for 48 hours when his lawyer (this was no longer the German Bossi, but Frenchman, François Gibault) requested bail. This was granted and the amount of bail the Mulhouse court demanded was the exact sum the police had found in André’s hotel bedroom - €19,000.

André, now 72 years old, faces 10 years in prison for kidnapping, but the legal experts are certain that he would receive only a suspended sentence of 18-20 months.

There were three kidnappers. One, a Kosovar (it is presumed that he is Anton), surrendered to the police in Austria. He has also been released on bail. The legal authorities of Austria, Germany and France would have to work out which of the three countries would put him on trial. The other two, one said to be French and the other German, are now on the run just as the man they had kidnapped had been. They have not been named.

For Krombach there will be a retrial here in France. Legal experts say that this time he would have to serve his time which will probably be more than the 15 years he had been given 14 years ago. At 74 years of age he is unlikely to ever leave jail. He is being held in La Santé prison in Paris; his lawyer, Frenchman François Serre had lost his appeal for bail for reasons of age and health.

The German Foreign Ministry has meanwhile made lukewarm efforts to have Krombach released and returned to Germany. A spokesperson for the Ministry said that Germany could not accept the abduction of an innocent German national; the legal authorities in Germany still consider Krombach innocent.

No one in France agrees with the German legal authorities, but they do agree with André. He says that what he had done should not be called an act of revenge. It was an act of justice. The French say so too. Danièle, who has remade her life with another man, has remained silent, but as André told journalists, she has always been against his campaign for justice for Kalinka; she believes that he should allow their daughter’s soul to rest in peace. As for Nicholas, Boris and Diana, they are all three now in their early forties and they too have moved away from that fateful summer weekend in Lindau 27 years ago. The four would, however, have to be called as witnesses in Krombach’s new trial.

What to do about serial rapists?

At the time that the Kalinka Bamberski case hit the headlines, the French were asking themselves, as well as the government of President Nicolas Sarkozy, what was to be done about serial rapists. Too often a rapist had been released from prison for good behavior before he had served his full sentence, just to seek another girl or boy, even toddler, to rape.

There was one particular case. Francis Evrard, 63, had, since 1975 and until July 2007, served time almost constantly for three different child sex convictions. Released that July 2007, he had again immediately kidnapped and raped a 5-year-old boy. He had grabbed the little boy at a country fair in northern France and had kept him locked up in a garage where he had performed various depraved sexual acts on the child. He was apprehended because a taxi driver had gone to the police when the child’s photograph was flashed on TV screens and he recalled that he had driven a man with a crying child to that garage; Evrard, on his release from prison, had started to squat in the garage which was in the garden of a derelict house.

Incarcerated, Evrard had begun to petition the Ministry of Justice to allow him to undergo castration. Consented chemical castration for rapists was already allowed in France. This was not what Evrard wanted however. He was asking for a physical castration. As he would say, only a physical castration would free him of his demons and would prevent him from raping a child yet again. Most French wanted him to be granted his wish, especially when they learned that on his release from prison in July 2007, the prison doctor had prescribed Viagra to him. He had told the doctor that he had an erection problem and if this could be solved with Viagra then he would be able to have sex normally with a woman and he would not have an urge to molest children. Accordingly, on his release from prison, he had gone straight to a chemist where he had been given two packets of Viagra: The result was that he had kidnapped and raped the 5-year-old boy.

French Parliament is to debate making consented physical castration of serial rapists legal. The parliamentarians will at the same time debate whether chemical castration of serial rapists should be made compulsory. Most French are however saying that as chemical castration is reversible – it involves the administration of drugs that lowers the sex drive – it will not serve any purpose, and therefore serial rapists should be physically castrated even against their will.

France is not the only European country to allow consented chemical castration. So do Sweden and Denmark. And a 63-year-old Swiss father and grandfather was recently physically castrated on his demand in the Swiss town of Neuchatel although he had never raped anyone. Henri Monod had claimed that his sex drive was so strong that it had turned his life into a hell. He told journalists that on a steaming hot day he would be lying in a bundle under a blanket, trembling from head to toe, trying to control his sexual desire. He had already tried chemical castration, but it had not worked. Monod, whose wife agreed with the physical castration, now counsels men who wish to undergo the same surgical procedure. He told journalists: “I should have had the procedure done years ago. It would have allowed me to use my energy in a more constructive way than having sex.”

As for the serial rapist, Evrard, his wish for physical castration was not granted and he and all his body parts are now serving a life sentence.

Two new trials

On Tuesday, March 29, 2011 a nervous but satisfied André Bamberski arrived at Paris’s High Court, the Palais de Justice. It was spring but a cool wind blew from the River Seine that borders the building. The day for which he had waited for the 29 years of his little girl’s death and which he had made sure would happen 17months previously when he had Dieter Krombach abducted and brought to France, had arrived. Krombach’s trial was to commence.

Krombach, a frail and bent figure, gripped the ledge of the box of the accused in the Grande Salle and told the court, “I did not kill Kalinka. I want to stress that I am not guilty, that I did not kill Kalinka and that I did not rape Kalinka.”

André, a civil party in the case, sat in the front pew of the gallery. So did Danièle his ex-wife – and that of Krombach too. Having remarried, she no longer supported Krombach; she was also a civil party in the case “to find out the truth,” as she told the media.

All of this first day of the trial Krombach’s lawyers fought to have the case thrown out on the grounds that a German court had declared that there was no case against the doctor. They failed. The Prosecution had new witnesses and it was certain that their testimonies would send the doctor back to jail for the rest of his life.

For the following days as the case progressed, Krombach visibly paled and aged, at times gripping his chest as if he was willing his heart not to give up on him. That he would suffer cardiac arrest was a possibility as the Defense emphasized, and on Tuesday, April 5, he collapsed in a disheveled bundle in his box and the case was adjourned until a later date which was still to be decided. Two days later, Krombach in the Pitié-Salpetrière Hospital, machines breathing for him and keeping his heart ticking, the court suspended procedures for 6 months.

Wednesday, October 5, the trial recommenced.

In the 6 months which had passed, Krombach had either been in hospital or jail, and he looked little fitter than back in April. He walked into court leaning on a cane. He again pled not-guilty. He spoke in French, his voice, hoarse. He could switch over to German whenever he wished as a German/French interpreter was at hand.

At the end of the day a rare supporter - his daughter from his first marriage – told journalists, “You saw how he was talking, if you’re telling me you think it’s possible for him to hold on for three weeks, there’s no chance.” The case was expected to last for three weeks. One of his lawyers, Laurent de Caunes, on the contrary told journalists that in his opinion the doctor did not appear “very feeble.”

André Bamberski also had a word for the journalists. “It’s certainly not revenge, it’s perseverance on my part,” he said of the trial.

A few days into the trial a 42-year-old German woman, Svenja Mauer and her 41-year-old sister Jana, told the court of how Krombach had sexually assaulted them when they were respectively 16 and 15. He had become their divorced mother’s physician and then her lover and a kind of substitute father for the two girls. On a vacation in France he had booked just one room for the four of them and as there was just one bed (a double) in the room the four had to share the bed. The first sexual aggression had occurred on the first night of the vacation. The two women said that later when Krombach had again accompanied them and their mother on a vacation to London, he had given them injections after which they had fallen asleep for several hours. They thought that he then had full sexual intercourse with them.

During her testimony, Svenja Mauer turned and looked straight at Krombach. “Why did you make young girls go through this?” she asked him.

His reply was directed to the well of the courtroom and not to her. “I did not have sexual relations with the Mauer sisters. They are lying.”

In 1997 when Krombach was on trial in Germany for the rape of a 16-year-old female patient, he had already made that denial and then the German police had believed him and had not charged him for the rape of the two sisters.

Danièle was also a Prosecution witness. She spoke of how Krombach was always attracted to the “unusual”. Of her daughter’s death she said that the doctor had injected Kalinka for her anemia after supper on the night of her death. “It was his fetish drug. He gave it to hundreds of patients,” she said. He also gave her an injection which had sent her to sleep. When she woke in the morning, Kalinka was dead. On seeing her daughter lifeless in bed, she said, “I immediately thought of the injection, but Dieter Krombach told me, ‘No, there’s never been any problem with these injections’.”

Why did she support him at first she was asked.

“At first I wanted to support him against Bamberski,” she began and added, “I learned things that worried me. That he had given me sleeping pills to have sex with a girl, a teenage neighbor, in our house. If you can do it once, you can do it other times. I have doubts for sure about why I slept so deeply that night.”

Germany had an observer in the court room and he like everyone in the gallery heard the verdict pronounced late in the afternoon of Saturday, October 22.

Krombach was found guilty of “willful violence leading to death without intent.”

The judge upheld the15 years of incarceration the court had sentenced Krombach to in absentia in 1995.

“In a way 15 years is a death sentence,” observed a French reporter referring to Krombach’s age - 76 - and his poor health.

Not quite the end yet

No sooner had the judge pronounced the sentence than Krombach’s lawyers lodged an appeal. In France an appeal case could take up to 18 months to be heard.

André Bamberski must also still have his day in court for having organized the abduction of Krombach. This case will not be heard until early in 2012.

Finally: Closure

On Friday, May 23, 2014, the still mourning André Bamberski, in the gray striped suit he had worn on Saturday, October 22, 2011 when Dr. Dieter Krombach was found guilty in Paris of the murder of Kalinka and sentenced to 15 years in jail, heard the chief judge of Mulhouse pronounce a guilty verdict on him too. His trial was being held in the town of Mulhouse in the province of Alsace because it was there that the kidnapped Krombach had been dumped on a street.

André Bamberski, finally, after more than a two-year wait for his trial, was found guilty of having ordered the abduction of his daughter’s killer. So too were two of the three kidnappers – Anton Krasniqi, a 43-year-old man from Kosovo and Kacha Bablovani, 28, from the former Soviet republic of Georgia. The police had not succeeded in apprehending the third kidnapper, identified only as Yvan. As Krasniqi and Bablovani testified, Yvan was the one who had beaten up Krombach. Photos of the doctor’s bloodied face were shown in court. Also on trial was a fourth accused: a 54-year-old Austrian journalist named Adelheid Rinke Jarosch. A friend of Bamberski, she had put him in touch with Krasniqi and Bablovani.

The prosecutor, in his summing up, asked for compassion for Bamberski in the form of a lenient sentence. He suggested a six-month suspended sentence.

A month later, on Wednesday, June 18, Bamberski and the three co-accused were back in the Mulhouse court to learn what sentence the French justice system thought they deserved. Five years have gone by since the kidnapping of Krombach, and 32 years since Kalinka’s death. Had her step-father not ended her life, she would have been a woman of 46 on that June day of the sentencing.

Bamberski was given a one-year suspended sentence.

The two kidnappers were each given a one-year prison term.

The journalist heard that no action would be taken against her.

As Krasniqi and Bablovani had already spent more than a year incarcerated while awaiting their trial, they left the courthouse free men.

Outside the courthouse Bamberski embraced Krasniqi, a father of three.

Said Krasniqi: “If I have to do it again, I will do it again.”

Krombach not happy in jail

Krombach had lost his appeal against his 15-year-sentence, and so he had a second appeal to France’s Court of Cassation, the State’s supreme court of appeal. He was to remain in Fresnes Prison outside Paris. There, at the end of September 2012, another inmate serving life for murder, beat him up. His request to be moved to Paris’ La Santé Prison to be kept in the safety of isolation was refused.

Now a movie

Later this year a movie of the case is to be shot in France.