June 26, 2012 Special to Crime Magazine

An excerpt from The Charmer: The True Story of Robert Reldan – Rapist, Murderer, and Millionaire – and the Women who Fell Victim to his Allure

(Title Town Publishing, 2012, available in soft cover at major book stores and in Kindle at Amazon.com.)

by Richard Muti and Charles Buckley

Preface

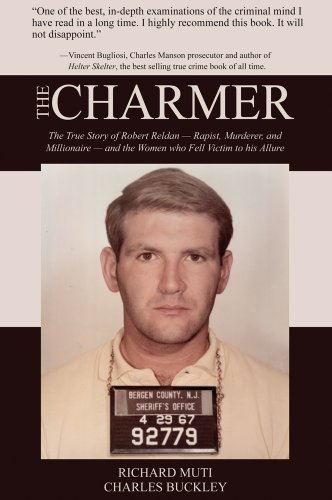

Bob sports that collegiate look.

It is not a monster's face that looks up at the reader, there on page 31 of the Fort Lee, New Jersey, high school yearbook, class of 1958; rather, the young man appears as carefree as any 17-year-old should be. Yet, at the time this photo was taken, Robert Reldan already had a troubling juvenile record, including the assault and robbery of a woman in New York City, and he had done time in a reformatory. His classmates surely knew his history, yet whoever wrote Reldan’s yearbook entry was kind.

"Bob sports that collegiate look," the blurb below his picture reads, a reference to what a later generation would call “preppy.” He is an amateur pilot, it says, and intends a stint in the Air Force. The only glimpse into future reality is a remark about Reldan's "acid sense of humor." Although young Robert had athletic ability, especially in basketball, school activities are sparse. Understandable, when the youth's extracurricular interests lay elsewhere.

It is a handsome face with an engaging smile—a smile that promises a charming personality and inspires trust. A smile that would, over the next 20 years, cause unsuspecting women to drop their guard and place themselves under the power of one of New Jersey's most ruthless criminals.

Robert Ronald Reldan was born in Brooklyn, New York, on June 2, 1940, the first child of William and Marie Reldan. Three years later, a daughter, Susan, was born into what was, by all appearances, a hardworking, middle-class American family. The Reldans operated the Sweet Sue Coffee Shop, a bustling establishment one block from New York City’s Fifth Avenue and its fashionable department stores. Marie doted on Robert, her only son, but the relative who would figure most prominently in Robert's life was his Aunt Lillian, Marie's sister.

Lillian Vulgaris was an aspiring actress, but, like most newcomers to that profession, she needed to support herself with less glamorous work until her big break came along. Brother-in-law William Reldan was happy to give her a job waiting tables in his coffee shop. While not beautiful, Lillian did possess an attractiveness and warmth that made her popular with patrons of the Sweet Sue, among them an older man—"Colonel" Ferris Booth.

Ferris Booth's father was a financier and early investor in IBM and Hotpoint Appliances. He made millions on those and other shrewd investments and would leave a fortune to his son. Lillian Vulgaris's big break came sooner than expected—not on Broadway, but when she caught the eye of Ferris Booth. The two were married and enjoyed a loving relationship for 10 years.

When Booth died suddenly of a stroke in 1956, 40-year-old Lillian inherited $50 million. By the time she, herself, died 51 years later, Lillian Vulgaris Booth, a shrewd investor in her own right, would quadruple her wealth, even while donating millions to hospitals and churches, a retirement home for aging actors, and other charities. Having no children of her own, she lavished attention and financial favors during her lifetime on nieces and nephews. Her particular favorite was Robert Reldan, whom she called "Bobby."

In 1951, when Robert was 11, the Reldan family moved from New York to Fort Lee in Bergen County, on the New Jersey side of the George Washington Bridge. With their proximity to New York City and location atop the Hudson River palisades, Fort Lee and its neighboring communities to the south would soon see a population explosion, as high-rise apartment buildings affording spectacular views of the metropolis across the river began to proliferate.

Robert Reldan had everything going for him early in life—innate intelligence, good looks, and a loving and supportive family, including his wealthy aunt, who not only idolized him but was generous with her money. Yet, something was driving him toward a darker world, one beyond the ken of most teenagers.

Chapter 1

He had the look of someone who could kill without remorse.

Fourteen-year-old Anna Maria Hernandez awoke to the sound of her dog barking. Glancing at the bedroom clock, she saw it was 3:20 a.m., but she wasn't alarmed. Her dog barked at the slightest provocation, and it wasn't unusual for her sleep to be disturbed. She got out of bed and went to the window to see if something outside might have aroused the animal. Seeing nothing, she quieted the dog and returned to bed. Moments later, she heard a sound coming from the kitchen. Thinking it might be the dinner dishes settling in their drain, she arose again to have a look.

Anna Maria lived in the Fort Lee home of an older married sister, Tomasa Suarez, but both her sister and brother-in-law were in Spain on business. So, on this early Sunday morning, February 25, 1962, the high school freshman was being looked after in the Suarez home by another sister, Leonor Munoz.

In the hallway near the kitchen, Anna Maria saw why the dog had been barking. There, inside her home, were two male intruders, their faces covered by pieces of cloth. The frightened girl began screaming, calling out to Leonor in Spanish. One of the men had a gun and the other an iron rod, perhaps a crowbar. They grabbed her by the arms, telling her to shut up and asking if anyone else was in the house. The girl said her sister and nephew were there, and the men went to a bedroom to get them, dragging Anna Maria along.

Leonor's immediate reaction—she had her 3-year-old son with her—was to lock the bedroom door. One of the men told Anna Maria they would kill her if the sister didn't let them in. He instructed the girl to tell that to her sister. Finally, with her child in arm, Leonor opened the door. The men pushed Anna Maria into the room, following her in.

One man had a handkerchief over his head, partially obscuring his face. The other had what looked like a bathroom towel over his head, with a narrow opening so he could see. The man with the handkerchief covering said, "Your brother-in-law is in Spain, right?" indicating knowledge of the household circumstances and lack of a male presence to challenge them. Both young women nodded, confirming that Francisco Suarez was away. The men demanded to know where "the money" was, but Leonor and Anna Maria denied knowing of cash in the house.

The man with the towel over his head took Anna Maria back to her room and began searching it, while the other remained behind with Leonor. The towel kept slipping from the man's head, allowing the girl to see his face. More than a year later, Anna Maria would identify Robert Reldan in a jailhouse lineup as the man with the towel over his head, the man who robbed the Suarez residence and sexually assaulted her that night.

The terror-stricken women watched helplessly as the intruders ransacked the place, looking for jewelry and money. At one point, Reldan was alone with Anna Maria in her bedroom. He tied her hands behind her back and her legs together at the ankles, then stuffed a sock in her mouth and put a blouse over her head, presumably to block her view of his face.

Anna Maria would later testify that the blouse was sheer and she could see him through the material. Reldan lifted the girl's pajama top to her neck and pulled her pajama bottoms down to her ankles. He then began touching and kissing her body. As the girl writhed in his grasp, Reldan struck her several times in the head with the iron rod, not enough to knock her out but enough to cause bruises. Finally, the accomplice came into the room and, seeing what Reldan was doing, said, "Leave her alone." The accomplice, clearly the leader, repeated his demand that Reldan stop sexually assaulting the girl, and Reldan complied. The two men left the house shortly thereafter, and the frightened women ran to a friend's home a few blocks away. Police were called, but no arrests were made at the time. The accomplice was never identified.

Sensing his absence from New Jersey might lessen the chance he'd be identified as one of the perpetrators of the Fort Lee home invasion, Reldan drifted for the next nine months, spending time in Connecticut and Missouri, where he enrolled, briefly, in a small college. His travels were financed by his family, including Aunt Lillian, whose generosity toward her Bobby apparently knew no bounds. In November 1962, Reldan turned up in southern Florida, and it didn't take long for the 22-year-old to run afoul of the law in that jurisdiction.

On November 30, Reldan was arrested in Miami Beach on a charge, ironically enough, of impersonating a police officer. A records check showed no criminal record. His previous escapades had all been dealt with through the juvenile justice system, or hadn't been detected yet, as with the recent Fort Lee burglary and assault. As far as any inquiring police agency could determine, especially one 1,400 miles from Reldan's home turf, the pleasant, cooperative young man in custody was a first-time offender.

Dade County authorities allowed Reldan to plea bargain the impersonating-an-officer charge just five days after his arrest, and the result was a 90-day suspended jail sentence. A month later, he was once again in Dade County Court for one of his favorite criminal activities—breaking and entering, or burglary. With just the impersonating charge on his record, as far as local police knew, he was able to achieve yet another plea deal that avoided incarceration. He pleaded guilty and got two years probation. Still no hard prison time, but Reldan was beginning to accumulate adult convictions.

Returning to New Jersey in the spring of 1963, Reldan continued his chosen path. He was arrested by Closter police on July 27, 1963 for carrying a concealed weapon—a handgun—in a motor vehicle. His long-suffering but loyal parents posted bail, and he was again released, pending grand jury consideration of the case.

Within a month, police in North Arlington, New Jersey, arrested Reldan on a charge of breaking and entering a residence, but this time the B&E included an assault with a tire iron on the woman living there. He was again granted bail until a grand jury could consider the two pending cases, but, prior to his release, Fort Lee detectives took Anna Maria Hernandez to the Bergen County jail, where she identified Robert Reldan as her assailant.

While the Closter weapon complaint and North Arlington burglary and assault were still pending further action by prosecutors, a Bergen County grand jury indicted Reldan, charging him with breaking and entering the Suarez home on February 25, 1962, stealing money and jewelry, and committing an assault with intent to rape against Anna Maria Hernandez. Reldan was arraigned on the indictment, and the matter was set down for a jury trial before County Court Judge Joseph Marini.

Robert Reldan's first adult criminal trial began on December 2, 1963, with Frank P. Lucianna, a prominent Bergen County attorney, hired to defend him. Representation like that does not come cheap, and Reldan, who had no job or money of his own, was clearly the beneficiary of his aunt Lillian Booth's generosity, once again.

The State presented just three witnesses—Leonor Munoz, Tomasa Suarez, and Anna Maria Hernandez. Both Leonor and Anna Maria testified that Reldan, the man seated in court at the defense table, was one of the intruders in their home during the early morning hours of February 25, 1962—the one, Anna Maria said, who had sexually assaulted her. She’d picked Reldan out of a jail lineup in August 1963, but admitted under Lucianna's cross-examination that she was shown a picture of the defendant by police before the lineup took place. There was no physical evidence or other corroboration to back up the testimony of the women.

Robert Reldan's first criminal trial resulted in a hung jury when the panel could not reach a unanimous verdict, either guilty or not guilty. The upshot of a hung jury is always a victory for the defense, because it forces the prosecution to choose among three equally distasteful options: try the case again, using additional criminal justice resources and the same imperfect evidence; offer up a more enticing plea bargain to the defendant; or dismiss the case outright as not being worth the time and expense.

In reading the trial transcript, one can see the skill of attorney Frank Lucianna having a bearing on the outcome, but he had help. Although a jury is supposed to base its finding on the evidence alone, the freshly scrubbed good looks of Robert Ronald Reldan, the alert, confident 23-year-old in the dock, clearly had an effect on the 12 men and women sitting in judgment. For a criminal defendant to get one hung jury was rare. This was the first of three hung juries Reldan would achieve over a long criminal career.

* * *

During this same period in 1963, New York City detectives were investigating a series of six assaults and robberies that occurred between June 4 and July 23—one in the Bronx and five in apartment buildings on Manhattan's Upper West Side. This was the general location of Reldan's first known juvenile offense back in 1957, when he was a high school junior. And the modus operandi, or MO, was strikingly similar.

In each of these Upper West Side crimes, a neatly dressed man—about six-feet tall, muscular, and in his early twenties—followed a lone woman into her apartment building's otherwise unoccupied elevator and politely allowed the woman to select her floor first. After making his selection for a lower floor and allowing the elevator to begin its ascent, the young man seized each victim by the throat and, while holding her that way to render her immobile, grabbed her pocketbook and any accessible jewelry. When the elevator arrived at the man's chosen floor, he stepped out, waited for the door to close—taking the stunned victim to her higher floor—and then fled the scene.

As might be expected, all five women assaulted and robbed in this manner were traumatized by the events. One victim remarked to investigating officers, "He [the attacker] had the look of someone who could kill without remorse."

Although efforts in the investigation initially concentrated on New York City, police were mindful of the crime locale's proximity to the George Washington Bridge escape route to Jersey. Good detective work eventually brought Robert Reldan to the attention of investigators. They used resources of the Bergen County Sheriff's Office to obtain a recent photo of Reldan, taken when he was arrested for the Closter weapons charge and the North Arlington assault and B&E, and assembled a photo array.

Detectives put Reldan's photo in with others having like characteristics and showed the lineup to victims of the elevator robberies, one at a time. All five women unhesitatingly picked out Reldan's photo and identified him as their assailant, as did the lone Bronx victim, a vending machine worker robbed at gunpoint of his night's collection proceeds.

On January 3, 1964, detectives arrested Reldan and charged him with the six New York robberies. When he was taken into custody, Reldan showed no remorse and tried to justify his actions by citing a need for money. It was a bogus claim, in that Reldan’s parents and Aunt Lillian still amply supported him. He had traveled the country and lived well for the two years he'd been out of prison, with no lasting job and no other means of support.

If money wasn't Reldan's motivation, perhaps a deeper force was driving him. With their ironclad case, NYC authorities didn't waste time pondering Reldan's psyche. But if someone had paid closer attention at this stage of the young man's criminal career, particularly to psychiatric reports warning of Reldan's "strong repressed hostility towards women," one has to wonder how the future might have changed. These New York assaults may have been the first indications that Robert Reldan could no longer contain his aggressive instincts against women.

Despite violent attacks on five women and the strong evidence against him, Reldan managed a lenient plea bargain in New York's Supreme Court, the trial-level court in that state. He was allowed to plead guilty to one elevator robbery (the other four were dismissed) and the Bronx robbery, and he was sentenced to two, five-year terms of incarceration at the Great Meadows reformatory, which housed other youthful offenders in addition to juveniles. Incredibly, the two five-year sentences were ordered to be served concurrently, not consecutively.

While serving his New York time, Reldan was brought back to Bergen County to answer for the Closter gun charge and North Arlington B&E, which also involved assault with a tire iron on a woman in the house he burglarized. Attorney Frank Lucianna arranged another plea bargain, in which Reldan pleaded guilty to the gun charge and burglary, but the assault on the housewife was dismissed. For good measure, the burglary involving the Suarez residence in Fort Lee and the sexual assault against Anna Maria Hernandez—the case that had resulted in the hung jury and that was still pending retrial—were also dismissed as part of the deal.

The judge imposed indeterminate sentences at Bordentown reformatory in New Jersey for each charge, but allowed those sentences to run concurrently with each other and with the New York sentence Reldan was then serving. The youth was returned to Great Meadows to complete his prison term.

Robert Reldan had committed a string of nine serious crimes as an adult—seven involving violence against women—and received, in effect, one five-year prison sentence. And it wasn't a forgone conclusion that he would be required to serve that full term. Early release is exactly what played out. Paroled on September 15, 1966, Reldan had served just over half his sentence. He was able to obtain this release from prison even though an early parole evaluation in New York concluded, "It might be essential to consider this case carefully . . . . In our opinion he will be a poor risk [for parole]. He has considerable potential toward criminal acts, particularly assaults . . . ."

Plea bargains are a fact of life in every state's criminal justice system. Simply put, there are not enough resources to bring every case to trial. Without the "let's make a deal" functioning of the justice system, courts would grind to a halt with a backlog of cases waiting to be tried. In the case of this particular plea deal in the summer of 1964, prosecutors in New York and New Jersey exercised poor judgment by allowing six offenses involving violence against women to be dismissed as part of the bargain—four of the elevator assaults in New York City, the tire-iron assault against the North Arlington woman during the burglary of her home, and the sexual assault against Anna Maria Hernandez. With the dismissal of those significant crimes, it was as though they never happened. Future judges passing sentence on Reldan would never be able to take those offenses into consideration. And future parole boards evaluating Reldan's fitness to rejoin society would not have those violent episodes as part of the man's conviction record, nor as the warning flags they should have represented.

Upon his release from prison in September 1966, Reldan returned to live with his parents in Closter while he looked for work. Maintaining gainful employment was a parole requirement, and Reldan was able to get a job as a clerk in a convenience food store near home. William and Marie Reldan continued to support Robert with free room and board and extra money whenever he needed it. They were encouraged when he appeared to stay out of trouble for five straight months—quite an accomplishment in the parents' eyes, considering his history. In late February 1967, they took him on a family vacation to Florida, where budding career criminal Robert Reldan met a girl and fell in love.

Chapter 2

Be quiet, I'm almost finished.

Bernice Caplan had a lot to be thankful for that April 27, 1967. She was happily married, with an 18-year-old son about to graduate high school and a 14-year-old daughter just beginning that time of life when mothers and daughters establish lasting bonds. Everyone was in good health, and there were no pressing problems. Life is good, praise God, she thought.

It was a beautiful spring day, the kind that invites anticipation of the warmth May and June would soon bring. Bernice was returning to her Teaneck, New Jersey, home after dropping off Passover cookies to her mother in nearby Hackensack. She arrived at about 3:10 p.m., the trip taking less than 15 minutes. Bernice parked in the driveway of the single-family residence and entered through a side kitchen door. After putting a kettle on for her afternoon cup of coffee, she immediately set about gathering the dirty clothing a family of four accumulates, with an eye toward doing a wash load before dinner.

Shortly after 3:00 p.m. that same day, Robert Reldan left the North Forest Drive home in Teaneck where he had been visiting with Renee Ross and her mother. He had been dating Renee about five months and spent most of that particular day running errands with her. It was a hard time for Renee—she and her young daughter had recently moved in with her mother while her divorce was pending.

Reldan had a second love interest he was cultivating—Beverly Moles, a 21-year-old he met the previous October. He had only been paroled a month and was working in a food store. She came in to buy groceries one day, and they hit it off right away. Beverly was a bank teller in Fort Lee and lived with her parents in Closter, Reldan's hometown.

In fact, Reldan was juggling three romances at the time, two local and one long-distance. His third and newest girlfriend was Judy Rosenberg, an attractive 27-year-old he met on a recent Florida vacation with his parents. Judy was staying at the same hotel with her 4-year-old son, Eddie. Her husband, Alan Rosenberg, was back in Chicago, under indictment and not able to leave Illinois—a circumstance Judy didn't mind. She was happy to escape his abusive control. When she met the handsome and athletic-looking Bob Reldan at poolside near the end of her vacation, she was immediately interested. They chatted and flirted that first afternoon, and Judy would later admit she fell in love with Bob almost from the first moment she saw him.

Not long after Judy Rosenberg and the Reldans returned to their respective homes—Judy to the lingering cold of Chicago in early March and Bob and his parents to Closter—Bob got a call from Judy. Her husband Alan had been murdered, his body found in the trunk of his car, riddled with seven gunshot wounds. Judy—frightened to death because of her husband's ties to organized crime—begged Bob to come to Chicago and stay with her and Eddie for a few days.

Reldan's unexplained absence from work to see Judy in Chicago had cost him his job. His boss was a good guy and probably would have given him the time off, but Reldan wasn't supposed to leave New Jersey under the terms of his parole and didn't want to go on record with his boss as having done so. The vacation with his parents had been approved by his parole officer, but an unsupervised trip to comfort a woman whose husband had just been bumped off, mobster-style, would not have been approved. So, he hadn't bothered to ask permission.

As he drove home from Renee's house, Reldan felt a mounting depression over his poor financial state. His Aunt Lillian's $1,000 Christmas gift had already been expended, and Reldan was subsisting on unemployment insurance and $50 a month from a worker's compensation claim. His aunt had also given him a new Volkswagen convertible when he was released from prison, and, while appreciative for that means of transportation, he often sulked at the thought of her immense wealth and the meager amount she seemed willing to part with for him. Each of her gifts only bred more resentment in him, and now, with no job and no ready cash, he was more depressed than ever.

Reldan's impending return to Florida was also on his mind. William Reldan was opening a restaurant there and had asked for his son's help in setting things up, an unpleasant prospect in the younger Reldan's mind. He and his father hadn't gotten along since high school, but he felt he owed his father enough to give it a try. As Reldan stopped at a T-intersection, waiting to turn north on Windsor Road, his most direct route back to Closter, he would have been in position to see Bernice Caplan pass by—the timing was right and the paths both individuals would have traveled to get to their respective destinations were right.

Why Reldan selected Bernice Caplan as his prey is a matter of conjecture, but his future behavior in this regard supports the theory that it was simply a random choice. She happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Reldan followed the woman north on Windsor Road in Teaneck that afternoon and saw her turn onto Briarcliffe Road, where she lived. There was no other reason for him to be on that quiet residential street. Robert Reldan saw that Bernice Caplan was alone and vulnerable; he followed her and watched as she walked from her car to the house.

Reldan drove around for a time, mulling over what he was about to do; then, he parked in front of the woman's home, a scheme to gain entry already formed in his mind. From the back seat of the car, he grabbed a suit he had picked up at the dry cleaner's earlier that day. It was still wrapped in plastic. Draping it over his arm, Reldan approached the front door and rang the bell.

Hearing the doorbell, Bernice set down her coffee cup and wondered who might be calling on her. It was too early for the kids to be coming home from their after-school activities, and they would have entered the side door, anyway. She went from the kitchen to the front door and, peering through a small window, saw a well-groomed, pleasant-looking young man, dressed in a light-colored windbreaker and checked pants and holding what appeared to be dry cleaning. He was about six-feet tall and had a muscular, athletic build.

Bernice opened the door slightly. Before she could say anything, the man spoke.

"Brantley?" he said.

Somewhat confused but certainly not alarmed or on guard, Bernice just stood there for a moment, not responding.

"Brantley?" the man repeated, with an expectant smile.

Bernice smiled back and, recovering her composure, said, "No, I'm sorry, you must have the wrong house. This is the Caplan residence, but there are no Brantleys in this neighborhood, as far as I know." It was then Bernice noticed a green convertible with a white top parked at the curb in front of her house. She would later describe the car as "new, very clean, very shiny."

Now it was the young man who put on a confused air. He asked Bernice if he could use her phone to call his employer and get the correct address for the delivery.

Bernice was reluctant to let a stranger into her home, but lulled by his clean-cut look and polite manner, she decided to go with her positive instincts. Stepping aside, she pointed toward the den, where the phone was, and told him to go ahead and make his call.

Reldan put down the suit he was carrying, went to the den, and pretended to make a call. The phone company would later report the call was discontinued in a second or two. After a few moments, Reldan came out of the den and told Bernice his boss wasn't in and he couldn't get the information he needed. Bernice checked a local directory to see if she could assist in finding the right address. She asked if the name was "Brandt." No, Reldan said, it was "Brantley," spelling out the name. Bernice found no such listing in Teaneck.

Reldan then walked toward the front door, with Caplan following. Before they reached the entryway, he spun around and grabbed the startled woman. He turned her so her back was to him and, in what seemed like a practiced and familiar move, roughly placed his left arm around her neck, locking the woman’s throat in the crook of his arm.

"Don't scream or I'll kill you," he said. He then demanded money.

Stunned and terrified, Bernice Caplan struggled, using both hands to try to break the vise-like grip around her throat, but Reldan was too strong. His hold got tighter and her breathing more restricted. Still demanding money, Reldan pushed the woman toward the back of the house, stopping near a wall between the den and bathroom. Bernice cried out that her pocketbook was in the kitchen, and he could have all the money she had. She would later tell investigators her attacker no longer seemed interested in money.

Shoving Bernice Caplan's face against the wall, Reldan slid his left arm down and grabbed her throat with his left hand, increasing pressure on the still struggling woman. Bernice could feel Reldan reach under her dress with his right hand and pull down her girdle and panties. She then felt his penis thrusting between her legs and against her vagina. Later, at trial, both she and a medical expert would testify that vaginal penetration had occurred, a necessary element to prove a rape had been committed.

During the sexual assault, Caplan repeatedly begged her assailant to stop, crying, "Why are you doing this?"

Reldan replied, "I'm crazy, don't you know."

When Caplan warned that her son would soon be home from school, perhaps hoping that information would get the madman to stop what he was doing to her, Reldan said, "If that boy walks through the door, I'll kill him. I have a gun in my pocket."

Continuing his sexual assault, Reldan told her, "Be quiet, I'm almost finished." He never released his chokehold on her throat during the rape. The more she tried to scream or break free, the stronger his grip became. Caplan would later tell police, "His fingers seemed to be searching for something in my throat." The chokehold tightened as her attacker neared his climax.

Reldan ejaculated on his victim's buttocks and then directed her to go into the bathroom and "clean up." He told her not to try to escape through the bathroom window, or he would kill her. Locking herself in the bathroom, Bernice waited in fear until she thought her assailant had fled. She opened the bathroom door, but to her horror, the man was still inside the front door. He turned and coldly stared at her for what seemed like an eternity but was more likely seconds. Bernice knew she would never forget that look or the man's face. After he opened the front door and left, she ran to the den and called police.

As the rape was taking place, before Reldan made good his escape from the scene, a 14-year-old neighborhood boy was walking past the Caplan residence on his way home from school. The youngster, a self-proclaimed sports car enthusiast with a special interest in Volkswagens, took notice of the green convertible parked in front of 330 Briarcliffe Road. Later, at trial, the teenager described the vehicle as "a nice, shiny car." He also reported that there were two distinctive decals on the back of the vehicle and later used that fact to positively identify police photos of Reldan's car as the vehicle he saw that day, April 27, 1967.

Teaneck police began calling Volkswagen dealers in Bergen County and checking motor vehicle records to identify owners of late model green convertibles fitting the description they had received. They turned up the name of Robert R. Reldan, a Closter resident. By contacting detectives in that town, investigators learned about Reldan's extensive criminal background, especially as it related to assaults on women. They also found out he was on parole from New York State, something that would enable them to force his appearance at police headquarters. Believing they had their man but wanting a positive identification before making an arrest, Teaneck detectives asked their Closter colleagues to call Reldan and have him come to their headquarters that evening—April 29—for questioning on some unspecified criminal matter. As a parolee, Reldan had no choice but to comply.

The detectives transported Bernice Caplan to the Closter police station, where Reldan was being kept in an enclosed room, visible only through one-way glass. Upon spotting Reldan, Caplan immediately and emotionally identified him as her attacker. She also saw Reldan's car in the police parking lot and spontaneously identified it as the vehicle she saw parked in front of her home before the assault.

Reldan was arrested on the spot and taken to the Bergen County jail, pending a court appearance on the charge of rape. Despite frantic attempts by his family to get him released on bail, Reldan remained locked up, primarily because New York State authorities filed a “detainer” against him as a parole violator.

On June 2, 1967, Robert Reldan's 27th birthday, a Bergen County grand jury returned an indictment charging him with raping Bernice Caplan. He was arraigned on that charge—a formal procedure in which a defendant enters a not-guilty plea—on June 9, and the matter was listed for trial the following month.

Thomas M. Maher, an accomplished member of the criminal defense bar in Bergen County, represented Reldan. It was just the second time Reldan would be facing a jury, the first time being the Fort Lee home invasion and sexual molestation case four years earlier, a trial he won by getting a hung jury. Assistant Prosecutor Thomas J. Ryan presented the State's case, which began on July 13, 1967, before County Court Judge John Shields, sitting in Hackensack.

The State's proofs consisted largely of the testimony of Bernice Caplan and Keith Strickland, the boy who observed Reldan's car in front of the Caplan residence. It included Mrs. Caplan's identification of Robert Reldan as her attacker, a fact she was absolutely certain of. The physician who examined Mrs. Caplan after the rape also testified as to vaginal penetration.

This was an era before the science of DNA identification, and lab work was not as conclusive as it is today. Nevertheless, a state police lab technician testified that semen was detected on the dress Bernice Caplan had been wearing when the attack occurred and that semen was also detected on tissue paper discovered in the pocket of Reldan's tan windbreaker. Also, human hair found on Reldan's jacket was of the same color and texture as Caplan's hair. That was as precise as forensic science would allow in 1967.

Reldan's attorney could offer no testimony to rebut the State's medical and lab evidence, but did call Reldan's two girlfriends—Renee Ross and Beverly Moles—to the witness stand to provide an alibi for him. Renee testified that Reldan left her house at 3:10 p.m. on the day of the rape. (Her mother, also a witness, put the time closer to 3:05.) Beverly Moles said that, at about 3:30 p.m., as she was leaving work for the day, Reldan showed up unexpectedly at the bank parking lot in Fort Lee where she worked though they had no plans to meet that afternoon.

By Monday, July 17, witness testimony was completed and all evidence presented. The lawyers delivered their summations, each carefully laying out for the jury what he considered strong points of his case and weak points of his opponent's case. It all hinged on whose testimony jurors would give the greater weight to: Bernice Caplan's tearful but unequivocal identification of Robert Reldan as her attacker, or the alibi provided by Reldan's two girlfriends. If the alibi witnesses were to be believed and Reldan was in their company at the times they specified, then he could not have committed the Caplan rape. There just wasn't time, considering the 15 minutes or so it normally took to get from Teaneck to Fort Lee.

As in every criminal trial, the burden of proof was on the prosecution, and that burden had to be met beyond a reasonable doubt, a legal concept that defies precise definition and is often confusing. All that was left was for the judge to give his charge to the jury.

Robert Reldan's jury took the Caplan rape case from the judge at 2:05 p.m. on Monday, July 17, 1967. After deliberating less than two hours, they were back in court telling the judge they were deadlocked. Judge Shields gave them the standard "jury deadlock" charge and sent them back to their deliberations, but it was no good. They were back less than an hour later, insisting they could not reach a verdict.

Reldan had won again—the jury was hung, and a mistrial declared by the judge. The handsome young man with the "collegiate look," despite a positive, in-court identification by his victim, somehow avoided a conviction—at least temporarily. One or more jurors disregarded Bernice Caplan's identification and chose to believe that the clean-cut preppy seated confidently next to his attorney, with his supportive family in the row behind him, could not have committed so evil a crime. And he didn't even have to take the witness stand, where he would have been subject to cross-examination by the prosecutor and where his prior convictions could have been used to impeach his credibility.

On September 25, 1967, Reldan's re-trial for the Caplan rape began before Judge Arthur J. O'Dea. On the first morning, Reldan requested permission to fire his experienced defense attorney, giving "drastic changes in circumstances" as the reason. Reldan refused to specify what those circumstances were, and Judge O'Dea properly denied his request. This was a gambit Reldan would use again in his criminal career in an attempt to delay trial proceedings against him. Delay frequently works in favor of a criminal defendant and against the State. Memories fade, witnesses disappear, evidence sometimes gets misplaced, and defendants reap the benefit.

The second trial also lasted three days, but First Assistant Prosecutor Fred Galda—a tough, take-no-prisoners litigator who would later have a long and distinguished career as a judge—prosecuted the case. With a different prosecutor, a different judge, and a different set of jurors in the box, justice was served. The jury convicted Reldan of all charges, and he was remanded to the Bergen County jail to await sentencing.

Convicted of a sex crime, Reldan was required by law as part of the presentence report to be evaluated by the State Diagnostic and Treatment Center in Rahway, New Jersey, to determine if he was a sexual predator. Three doctors examined him on October 18, 1967. They concluded that Robert Reldan "showed a compulsive pattern of sexual behavior" and noted that Reldan strived to be "ingratiating and manipulative," using terminology from psychology and psychiatry in an effort to impress his examiners.

The caseworker interviewed Reldan's parents and put together the presentence report. The family of an innocent crime victim deserves the sympathy and support of everyone connected with the criminal justice system, but one also can feel, at times, a legitimate regard for the criminal's parents, whose offspring has taken a path at odds with the way they had brought him up. It is difficult to feel any sympathy for William and Marie Reldan's continuing denial of reality. Their blind loyalty to their son, taking his side in every criminal endeavor he ever engaged in, actually facilitated Robert Reldan's lifetime of crime . . . and resulted in a tragic aftermath of brutalized female victims. The presentence report said that Reldan's parents "maintain[ed] their son's innocence in regard to the charge of rape." They were hoping the court would not incarcerate their son and had arranged to have him admitted to a private treatment facility in Canada, if he could be kept out of prison. "They understand that the boy has a mental problem," the report continued, "and they are very distraught over this whole matter." But the report went on to state that the parents "cannot picture their son committing this offense, as he has many girlfriends and, further, that he did not need money."

The report recommended Reldan be sentenced in accordance with the New Jersey Sexual Predators Act, which specified "indeterminate" terms of incarceration at the State Diagnostic and Treatment Center, with a specified maximum. Following this recommendation, Judge O'Dea sentenced Reldan to an indeterminate term at the Rahway facility, not to exceed 30 years.

After sentencing, Reldan's first stop was the diagnostic section of the prison, where he remained for four months while the evaluation process continued. Classified as a "special sex offender," he was transferred to the treatment section of the facility, there to begin psychological counseling and therapy to eliminate or, at least, bring under control his "repetitive, compulsive pattern of sexual behavior."

From the outset, Robert Reldan became a model prisoner/patient in the sex offender treatment program. He impressed the staff with his intelligence and eagerness to be cooperative and to learn. His attitude of superiority initially put off his fellow inmates, but they, too, were soon won over. Reldan eventually gained everyone's acceptance, it seemed. Even normally skeptical staff members were hard put to resist membership in the "Bobby Reldan Fan Club."

No one, however, was more taken with or charmed by Robert Reldan than William Prendergast, the assistant superintendent of the Rahway treatment unit. In time, the relationship between Prendergast and Reldan became so close that staff were concerned the unit's supervisor was neglecting other inmates to act almost exclusively as this one prisoner's full-time therapist.

In less than three years, Prendergast would become Robert Reldan's ticket to freedom and he would lead Reldan, inadvertently, to his next female victim.