Crime Magazine's Review of True-Crime Books

by Anneli Rufus

(Vol. 9, Oct. 5, 2002)

With international intelligence, infiltration, surveillance and secret weapons making headlines every day, we've come to see a whole new kind of crime as increasingly real, rather than the titillating yet comfortingly remote stuff of spy novels. New books such as Into Tibet, Blood Diamonds, The Hacker Diaries and Spy Dust explore the global scope and terrifyingly high stakes of international intrigue.

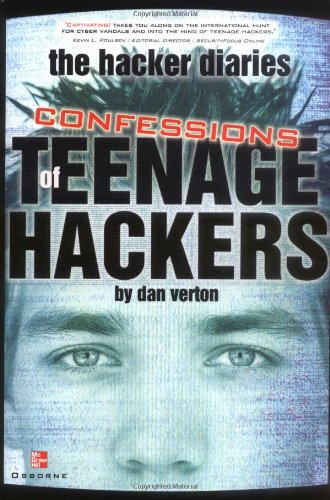

The Hacker Diaries, by Dan Verton. (McGraw Hill, 2002): A veteran high-tech reporter cracks into the stories of teens who have cracked into corporate computer systems and government databases, costing companies millions of dollars and endangering national security. While the details of exactly how they did it will sail right over the heads of any but the most computer-savvy, Verton's character studies of these underage perps — brilliant, bored, ambitious and dangerous — are an exciting new true-crime landmark.

Into Tibet, by Thomas Laird. (Grove, 2002): Just after WWII, CIA agent Douglas Mackiernan was stationed in far northwestern China, where his task was to keep track of Stalin's atomic-bomb tests. When Mackiernan was murdered, he became the first CIA agent ever killed in the line of duty. The author probed government files and conducted extensive interviews to unravel this exotic yet true cat-and-mouse tale.

The Common Hangman, by James Bland. (Zeon, 2002): Gross work if you can get it — this newly enlarged and graphically illustrated edition of a classic study explores actual hangmen from Tudor to Victorian times, featuring interviews, anecdotes, and firsthand impressions of capital punishment. The descriptions in this volume make it easy to see why public executions are no longer a staple in the civilized world, and make it all the more shocking that they are still common practice in some nations.

The Count and the Confession, by John Taylor. (Random House, 2002): Beverly Monroe, an ordinary middle-class, middle-aged divorcee, got a 22-year prison sentence for the murder of her lover, a self-styled Polish count with a vast Virginia estate who turned up dead of a gunshot wound one morning. Monroe was freed and exonerated after 10 years, but at an amazing personal cost. This true tale of half-blind justice will make you hope you're never charged with anything.

Demon Doctors, by Kenneth V. Iserson. (Galen, 2002): Power perverts the mind and corrupts the soul, as is proven by this international array of homicidal physicians. Among the many accounts in this quirky volume are those of a WWII-era Japanese army physicians who "experimented" on POWs, and Britain's Dr. Fred Shipman — who since his arrest in 1998 has been linked with hundreds of deaths, mostly of elderly but not seriously ill patients.

Blood Diamonds, by Greg Campbell. (Westview, 2002): Diamond smuggling, which Campbell discovered is often completed right under the complicit noses of the international diamond industry, has turned many African nations into war zones. Fighting over mine ownership and the gems themselves, ragtag armies slaughter civilians and conscript kidnapped children, turning them into exterminators. This investigative-reporting page-turner follows gems as they fund sinister causes — including Al Qaeda.

Spy Dust, by Antonio and Jonna Mendez. (Atria, 2002): The authors spent decades as high-level CIA agents, tracking missing persons and suspected KGB spies. As masters of disguise, they mounted countless secret operations. In this combined memoir, they explain how they did it, blow by blow, giving insight into international skullduggery in the twilight of the Cold War.

Heist, by Jeff Diamant. (John F. Blair, 2002): The $17 million heist at the Loomis, Fargo & Co. in Charlotte, N.C. in October of 1997 was the easy part. The hard part -- the impossible part as it turned out -- was sitting on the proceeds from the second largest theft in U.S. history. A video camera recorded Loomis employee David Ghantt carting the cash out of the warehouse for over an hour. Ghantt dumped the money with his co-conspirators and fled to Mexico with chump change, discarding his wife for a love fantasy with one of the conspirators. The FBI was stumped for a few months until the main conspirator -- who had tried to have Ghantt murdered -- began spending lavishly. A good subtitle for this quaintly written tale would be, "The Gang Who Couldn't Steal Straight."

(Vol. 8, July 1, 2002)

I'll Be Watching You, by Richard Gallagher. (Virgin, 2002): Stalking is one of the more invidious forms of pathology. Once in a stalker's grip, a living hell takes over the life of the prey. Gallagher details the lengths to which stalkers will go with accounts of a the young woman who befriended a lonely coworker only to find herself the object of his unwanted obsession for the next eight years; a noted violinist stalked by a fan for 14 years; a college teacher whose career was nearly destroyed by a student's relentless charges of sexual harassment.

The Poet and the Murderer, by Simon Worrall. (Dutton, 2002): Forgery is an interesting crime all by itself; the forgery of poetry makes it all the more poignant. The forgery of a poem by Emily Dickinson, one of America's greatest and most elusive writers, makes it a crime of international importance, and combined with homicide, it makes for one of the most fascinating books of the season. The setting skips back and forth between Dickinson's native New England and Utah, home of the brilliant perfectionist who also happens to be the titular murderer.

Fear No Evil, by Thomas Henry Jones. (St. Martin's, 2002): Three high-school boys in small-town Indiana viciously murdered a middle-aged man, basically because he was homosexual. The young killers — two star athletes and a wannabe gangbanger — came from disparate backgrounds, yet came together for this one fateful event. Veteran journalist Jones brings authentic personalities to the page while probing the homophobia that permeates fundamentalist Christian rhetoric: the crime's main instigator was a Sunday-school teacher ashamed of his own desire for young boys.

Women Who Kill, by Carol Anne Davis. (Allison & Busby, 2002): The distaff side of homicide is having its long-delayed moment in the sun. In this latest addition to the fledgling genre, a British author profiles a baker's dozen of deadly females on both sides of the Atlantic, including the ubiquitous Myra Hindley and Aileen Wuornos. It's always intriguing to learn about unfamiliar cases and criminals, but Davis's choppy style and grammatical lapses give these narratives an unprofessional feel that seriously undercuts the stockpile of interesting details within.

The Good Doctor, by Wensley Clarkson. (St. Martin's, 2002): As quietly fascinating as its subject, this page-turner tells a story that has held England in thrall for years — ever since family physician Fred Shipman came under suspicion for having killed hundreds of his patients, most of them elderly, with injections that aroused not a whiff of suspicion until long after their deaths. This tale of shattered trust and its lasting repercussions, not in a single family but throughout an entire town, reveals how much damage a lone killer can do, given enough time and the deft manipulation of power.

Into the Mirror, by Lawrence Schiller. (Harper Collins, 2002): FBI Special Agent Robert Hanssen comported himself as a devout Catholic and a staunch anti-Communist. Beneath that veneer he was a master spy who used his lofty position to sell state secrets to the Russians for more than 20 years. A devoted husband, he also pursued women as part of a double life that he maintained so scrupulously, for so long, that his arrest amazed nearly everyone who knew him. Based on an investigation by the New Yorker's Schiller and Norman Mailer, this biography tracks Hanssen from childhood, during which he was the frequent target of an abusive father, to his guilty plea on charges of espionage and beyond. Delving beneath the headlines, this forceful narrative exposes a genuine human being for whom power and control, rather than money, proved the ultimate lure.

(Vol. 7, April 27, 2002)

The Mammoth Book of Women Who Kill, edited by Richard Glyn Jones. (Carrol & Graf, 2002): This hefty A-to-Z's title tells it like it is: an encyclopedic collection encapsulating nearly 50 cases involving women scorned, dragon ladies, and ladies who lunch — but not without a bit of arsenic. Ranging from a French Revolution-era assassin to '70s sex-killer Rosemary West to serial murderer Aileen Wuornos, this new edition of the anthology offers a vast, if not terribly deep, perspective on the always fascinating but seldom discussed distaff side of homicide.

Labyrinth, by Randall Sullivan. (Grove/Atlantic, 2002): The still-unsolved murder of rap star Tupac Shakur in Las Vegas and that of his rival, Notorious B.I.G., in Los Angeles soon afterwards sparked storms of controversy that rage to this day. Entering a world of death threats, cover-ups, hit men and high rollers, Rolling Stone reporter Sullivan penetrated the scandal-plagued L.A.P.D. and gangsta-rap goldmine Death Row Records, ferreting out lethal links between the two that shed intriguing new light on the killings. Explosively brave, this page-turner of an exposé is a must-read for rap fans and Angelinos.

Cracking Cases, by Dr. Henry C. Lee with Thomas W. O'Neil. (Prometheus, 2002): Lee made national headlines when he testified during the O.J. Simpson brouhaha, which is one of five murder cases the amiable forensic scientist examines in detail here. Not for the squeamish are these tales of killers whose attempts to cover their tracks were dissembled, bone chip by bone chip, by the author and his colleagues. A refreshingly human and sometimes humorous look at the painstaking work of forensic researchers, the narrative nevertheless flags here and there when it veers from lively description to hard science.

I, by Jack Olsen. (St. Martin's, 2002): An ambiguous one-letter title undercuts the rare force of this reportorial adventure. Having interviewed at great length Keith Hunter Jesperson, the West Coast's notorious "Happy Face Killer," Olsen alternates between third-person narrative and first-person monologue in recounting this gritty tale of a murderous truck driver. The first-person sections are especially effective, affording an uncomfortably firsthand look at serial rape and strangulation. Raw and unfiltered, Jesperson's descriptions and logic comprise a riveting journey into the mind of a criminal who is neither a crazy genius nor a bumbling idiot, but a calculating chick-magnet and father of three.

Monstrous, by Tommy Walker. (GreatUnpublished.com, 2001): Offering yet more insight into the spirit's scariest recesses, this "autobiography of a serial killer but for the grace of God" mixes sardonic wit with vivid detail to track some very close calls. Starting with his perfectly ordinary birth, the pseudonymous Walker recalls his first murderous urges as a schoolboy and their progression into much more detailed plans. Living in an urban university district, the author nurtured homicidal fantasies, choosing locations and even victims. This is about as close as you can come to a murderer's mind, this side of murder.

Cries in the Desert, by John Glatt. (St. Martin's, 2002): If empathizing with the victims is a typical part of your true-crime reading experience, then be warned: Glatt spares few details when explaining how New Mexico park ranger David Ray and his fiancée Cindy Hendy tortured each of their young female victims for days on end in a remote trailer, employing cattle-prods, enormous dildoes, medical devices, and modes of confinement including handcuffs, duct tape, and a homemade coffin-like box. Despite the book's sunny setting, its evocations of the no-hopers who populate this tale create a mood of relentless darkness.

(Vol. 6, April 10, 2002)

Breaking Point, by Suzy Spencer. (St. Martin's, 2002): Andrea Yates was by all accounts a devoted parent, home-schooling her four small sons, inseparable from her 6-month-old daughter. She baked luscious birthday cakes and sewed adorable costumes. Having drowned all five children in the family's bathtub last summer, Yates is now the subject of raging controversy, whose many thorns and horns Spencer navigates skillfully concerning the case's early stages. Interviews with friends and family create a Rorschach-test image of a killer in whom clinical depression, a controlling husband, and religious extremism sparked the ultimate act of passive aggression.

Death Of A Doctor, by Carlton Smith. (St. Martin's, 2002): Recounting yet another out-of-nowhere murder, Smith tracks the case of Kevin Anderson, a popular Southern California pediatrician whose inability to say no — either in his business or sex life — led him to murder a fellow physician who was interfering with both. The story of Anderson's lethal affair with Dr. Deepti Gupta is intriguing for its cross-cultural ramifications, but otherwise offers insufficient material to fill a book. Pulitzer-nominee Smith makes a valiant effort, but Anderson is simply a rather dull character; key figures who could have filled out the story with satisfying depth refused the author's requests for interviews.

Crossing To Kill, by Simon Whitechapel. (Virgin, 2002): Newly updated by a British author – whose penchant for quoting from classic literature, often in Latin, will fascinate some readers but scare away others – this intriguing change of pace is an utterly spooky virtual excursion to Ciudad Juarez, a Mexican border town where some 200 young woman have been raped and murdered over the last 10 years. Not following a strictly chronological narrative, Whitechapel wanders down the story's weird avenues, introducing prime suspect Abdul Latif Sharif Sharif and the local gangs whom Sharif, long in prison, seems to have indoctrinated into continuing the bloody slaughter. The overall effect is that of a nightmare, largely for the picture it gives of a factory town where countless teenage girls earn three dollars a day and whose disappearance, often as not, goes completely unnoticed.

Crossed Over, by Beverly Lowry. (Vintage, 2002): Karla Faye Tucker murdered her former boyfriend and his new girlfriend with a pickaxe and then re-invented herself as a darling of the religious right on Texas's death row. In the weeks leading up to her execution by lethal injection in early 1998, her conversion from sinner to saint had petitions for clemency arriving at then Gov. Bush's office from all over the world. Subtitling this work "A Murder, a Memoir" when it was first released 10 years ago, novelist Lowry adds a new, post-execution foreword. Tucker thoroughly enchanted Lowry, who wrote this unsettling account of the ensuing relationship — which in turn was made into a TV movie that aired in March 2002. Even if the object of Lowry's admiration was not a killer-turned-proselytizing-convert, her besotted and toadying tone would be borderline unbearable.

The Surgeon's Wife, by Kieran Crowley. (St. Martin's, 2002): She nagged, she whined, she shopped a lot. He put in long, grueling hours at the hospital, pursued interesting hobbies — and strangled cats when he got stressed out. Dr. and Mrs. Robert Bierenbaum were not quite the perfect couple, and after she disappeared one summer day in New York, he got on with his life, though family and friends nursed dark suspicions. This story of a brilliant plastic surgeon's decade-long run from the law and eventual capture makes for breathless reading. Bierenbaum is a real-life character, richer and stranger than those in most fiction. Around him, Crowley has woven a compelling web of gossip, research, courtroom drama, and innuendo.

Booty: Girl Pirates On The High Seas, by Sara Lorimer. (Chronicle, 2002): They shot and slashed their victims and stole their loot. They raided passing ships and raised havoc. An international bevy of female freebooters gets a rather gentle treatment, all things considered, in this whimsically illustrated gift book. Characterized here as bold individualists and depicted in Easter-egg colors, 12 pirates, including Ireland's Grace O'Malley and China's Lai Choi San, are awarded high points for their leadership qualities and derring-do, all in a swingy style that evinces the fact that, for most of us, pirates of either sex no longer pose much of a threat. Most of these figures ended up at the gallows: in their day, piracy was anything but coffee-table fare.

(Vol. 5, Feb. 26, 2002)

Armed & Dangerous, by Gina Gallo. (Forge Books, 2001): A Chicago policewoman for 16 years before a near-fatal beating by an assailant with a baseball bat facilitated her departure from the force, Gallo has written a horrifying scrapbook of a memoir. Her narrative snapshots show the mean streets at their most senseless and relentless, whether it's the boy slaughtered in a stairwell for his Air Jordans or the 14-year-old mom who hides heroin from the cops by pouring it into the baby's formula, with lethal results. Literary for all its no-holds-barred brutality, the book treads suspiciously close here and there to urban legendry, such as when Gallo claims to have raided a Chinese restaurant that was serving up cats and dogs.

Public Enemies, by John Walsh with Philip Lerman. (Pocket Books, 2002): Fans of "America's Most Wanted" relish that TV show's unique blend of tenderness and aggression. Written in the same tone of righteous rage that distinguishes its scripts, with the same swift flow, this collection of high-profile cases revisits some familiar stories such as the Railroad Killer murders but goes behind the scenes to reveal, as Walsh is wont to say, "what went down" between "AMW" staffers, law-enforcement officers, tippers, survivors, and perps. In-depth detail brings victims heartbreakingly back to life while lending a 3D authenticity to all the people and places involved. It is this authenticity, and a firm refusal to tabloidize, that make both show and book formidable crime fighters.

Corpse, by Jessica Snyder Sachs. (Perseus, 2001): Like all the talented science writers whose work has been climbing the best-seller lists these last few years, Sachs brings an irrepressible enthusiasm to this study of forensic scientists' struggle to pinpoint the time of death. In clear language, she scans the careers of pioneers in the field -- bold scholars who devoted years to watching maggots eat flesh and, as a result, made crimes so much easier to solve. A crash course on postmortem biology, the book is remarkably witty even as it wades through several centuries' worth of carnage. A few actual cases come into its purview, but Sachs prefers the broader, bloodier tapestry of forensic science in general: this is a book not about who killed whom, or even why, but all about when.

Victorian Murders, by Rick Geary. (NBM/Comicslit, 1987): A veteran of National Lampoon and The New York Times, cartoonist Geary set his pen to creating true-crime comic books; this one is his fifth. Several cases get the blow-by-blow in this slim volume, based on old books and press reports, which merges terse and faintly ironic text with that flowing, almost-Art Nouveau drawing style which Geary made famous several decades back. A novelty that looks good but won't take long to read, it should remind all artists that true crime is too fascinating a topic to be confined to just plain books.

Alone With the Devil, by Ronald Markman, M.D., and Dominick Bosco. (Doubleday, 1989): As a forensic psychiatrist, Markman interviewed some of the last century's most notorious criminals, and testified at their trials as well. Here he tells the inside story, recounting the crime in question briefly, then revealing what killers like Kenneth Bianchi and Leslie Van Houten told him — and what conclusions he drew as a result. Included here are Sacramento's self-styled "vampire" and Marvin Gaye's minister father (who was also the singer's killer). The narrative's tendency to ramble might irritate some readers, as will the book's absence of an index, and clever but general chapter titles that offer no clue as to which individuals will be covered within.

Helter Skelter, by Vincent Bugliosi. (Norton, 2001): Bugliosi, a skilled prosecutor, made a new name for himself as a nonfiction writer with this book based on the Manson Family's 1969 Tate/La Bianca murders and their aftermath, in which the author took an active part. Those killings — as senseless as they were vicious, and carried out by the willing lovers of a mad hippie cult leader, with allusions to Beatles tunes written in blood — marked for many Americans the virtual end of the '60s. And with the decade went all its fond dreams of peace and love. Newly re-released, this true-crime classic is as hard to put down today as ever. Retrospect, in fact, is as revelatory as a new pair of reading glasses.

(Vol. 4, Jan. 30, 2002)

The Ultimate Jack the Ripper, by Stewart P. Evans and Keith Skinner. (Carroll & Graf, 2001): Skinner and Evans have been researching the Ripper case for more than 30 years. At nearly 800 pages long, their illustrated encyclopedia offers a chilling plunge into a case that has made hearts race ever since London prostitute Emma Smith turned up murdered and mutilated in April 1888. Photos and detailed descriptions of the corpses Jack left in his wake are here, along with police reports, letters, articles and extensive speculation on the killer's identity. While this undoubtedly won't be the last word on what even by today's standards was a shocking crime spree, these authors — one of whom is a retired British cop — have turned a lifetime of research into a landmark work.

Death at the Priory, by James Ruddick. (Atlantic Monthly, 2002): Sex drove many a Victorian Briton to extremes — leading, often enough, to death. Deciding to reexamine a 19th-century poisoning case that seized headlines in its time and made unwilling celebrities of everyone involved, journalist Ruddick gained access to documents that had been unavailable in the course of the original investigation. The revelations he found therein make this book no less of a page-turner than the character studies he crafted of both the victim and the various suspects. Sensitive yet coolly unsparing, these studies provide insight to a society that looks askance at extramarital affairs, abortions, and female lust. Dickens wasn't kidding.

Crimes of the Rich and Famous, by Carl Sifakis. (Checkmark, 2001): Organized as an encyclopedia, this work promises an A-to-Z accounting of high-profile mayhem. Covering not only Charles Manson and Ted Kaczynski but also extortionists, celebrity madams and other types of perps, Sifakis includes a hefty number of cases dating back a hundred years and more. Readers with a historical bent will find these worth their while, and worth trudging through the book's slipshod prose. Others will find themselves picking impatiently through page after page of nineteenth-century incidents in search of something vaguely contemporary. Even then, "rich and famous" comes across as a gimmick not all that convincingly carried through.

Who Killed Diana? by Peter Hounam and Derek McAdam. (Frog, 1998): When celebrities are involved, there's really no such thing as a cold case. Conspiracy theorists will find rich food for thought in the provocative questions raised here by two British reporters who believe that what happened in the Paris tunnel was no accident. Was there a contract on Dodi Fayed's life, they wonder, and was some shadowy figure determined at all costs to keep the future king's mother from converting to Islam? Was the driver of that doomed Mercedes poisoned? Urging readers to look beyond all official explanations, the authors provide plenty of colorful background on the ill-starred lovers' courtship and what might have motivated whom to do what.

Hong Kong Murders, by Kate Whitehead. (Oxford University Press, 2001): Capturing the Fragrant Harbor's unique character, this collection recounts crimes of passion, kidnappings and the gangland bloodbaths that have inspired countless Hong Kong movies. These tales of doomed tycoons, loose-cannon kidnappers, and spurned lovers — as well as a shy necrophiliac — are told intelligently, with an eye toward the former colony's culture and history. Ranging over the last 20 years, they reveal a seldom-seen side of those teeming streets and quiet shores, and the never-ending dramas on both sides of law enforcement.

Special Agent, by Candice DeLong. (Hyperion, 2001): Candice DeLong was one of the first women to make a career out of the FBI. This memoir incorporates her earlier experience as a psychiatric nurse into 20 years of tracking tough criminals, mostly in Chicago. She mixes cozy personal bits about being a single mom and dating a fellow agent with fast-moving crime stories. Comic relief peppers the text in the form of perps who can't think straight; they're a welcome contrast to DeLong's accounts of serial rapists and drug kingpins who, unfortunately, can.

(Vol. 3, Jan. 12, 2002)

Innocent Victims, by Brian J. Karem. (Pinnacle, 2001): Parents will blanch while reading this tale of yet another homicidal teen: a New Jersey suburbanite who murdered a child who was selling candy door-to-door. Neither concerned kin nor teachers nor counselors could save Sam Manzie from the middle-aged pedophile who seduced him in an Internet chat room and whose eventual in-the-flesh encounters with Sam sent the teen into an emotional tailspin that turned out to be lethal. This book shows what happens when the weak devour the weaker.

Murder at 40 Below, by Tom Brennan. (Epicenter, 2001): The 49th state is still a wild frontier, promising golden opportunity for some and solitude for others. That's what makes Alaska great, but -- as this collection of 10 recent true-crime tales shows -- it also makes Alaska deadly. Recounted by a longtime Anchorage reporter who knows his turf, these stories are set amid endless wooded splendor, last-resort strip clubs, and the sort of murder scene where victims stay hidden until the next year's thaw. Photographs would have brought the crimes more satisfyingly to life, as would smoother prose, but the book will intrigue anyone with Alaskan connections.

Internet Slavemaster, by John Glatt. (St. Martin's, 2001): Killers have come a long way since the simple days of blunt instruments and icepicks. Family man John Robinson moved on from bilking his Midwestern neighbors in false financial schemes to out-and-out murder. Showing how Robinson recruited women as sexual slaves on Internet bondage-and-discipline chat rooms, Glatt gives a rare glimpse of the thriving world of cybersex, illuminating its games of identity and fantasy.

Kill Grandma for Me, by Jim DeFelice. (Pinnacle, 2001): Barely 13, Wendy Gardner persuaded her 15-year-old beau James Evans to kill the grandmother who had raised her and who wanted the pair to break up. When the job was done, the kids snacked on burgers and shopped at the mall. Courtroom drama featuring fiery lawyers comprises a big chunk of a book that lets no one off easy, shining a bright and unblinking light on everyone concerned. DeFelice displays a rare knack for capturing the do-or-die, sex-scen helped cops track down Robinson, whom she suspected of killing her best friend; this unlikely heroine's courageous cat-and-mouse strategy gives the book a special heft.

Dead Reckoning, by Michael Baden, M.D., and Marion Roach. (Simon & Schuster, 2001): Taking us behind the scenes in the autopsy room, this bubbly offering from a 40-year veteran of forensic pathology squeezes in a fair share of chuckles amidst some truly harrowing imagery. Chapters deal with diverse aspects of Baden's work such as crime-scene investigation, the many virtues of maggots, and the proper dissection of severed heads. The authors also provide glimpses of famous cases in which Baden was involved, ranging from the Nicole Brown Simpson/Ronald Goldman killings to the mysterious death of casino heir Ted Binion. see An Early Grave to the search for Russia's Duchess Anastasia. Baden ties the latter in, interestingly, with a meditation on his own relatives' deaths at Auschwitz.

Rope Burns, by Robert Scott. (Pinnacle, 2001): A lesson in what happens when ne'er-do-well kids, left to their own devices, grow up into full-grown monsters, this page-turner leaves no one feeling safe. Being a young husband and father weren't enough for James Daveggio, who hooked up with a former prostitute and joined her in a kidnapping, raping and killing spree that terrified Nevada and Northern California during much of the '90s. Trolling the highways in a specially outfitted torture van, the pair assaulted not only strangers but also their own teenage daughters; this is a story that blasts holes in our basic ideas about how far even killers will really go.

(Vol. 2, Dec. 24, 2001)

The Adversary: A True Story of Monstrous Deception, by Emmanuel Carrère. (Picador, 2002): Due out in paperback in January, this meditation on murder was a major bestseller in France, where its author is a popular novelist and where the case it recounts was big news. Jean-Claude Romand began as a country boy so gifted that his parents sent him to medical school. But when it became clear that he would never graduate, he couldn't bring himself to tell them — or anyone else. Retracing Romand's web of lies, the years he spent posing as an elite physician while in fact spending his days in cafés and bilking relatives out of their bank accounts through fake investment schemes, the author is clearly both impressed and repulsed. Webs are sticky, though: When Romand's family was about to uncover his ruse, he committed five murders rather than tell the truth. Following his trial, its aftermath and the letters between killer and author, Carrère creates a character study which, revealing as it is, will prove too philosophical for some.

Shots in the Dark, by Gail Buckland, with commentary by Harold Evans. (Bulfinch, 2001): Packed with crime-scene photographs that etch themselves instantly on the mind's eye, this picture book based on a Court TV documentary lavishes exquisite production values on a topic that seldom gets such fine treatment. Some are effectively stark while others are achingly subtle, but these black-and-white images transport us to dire moments, dire places: The dead Sharon Tate is here, as are Lizzie Borden's parents. Illustrated with autopsy photos, an entire chapter deals with JFK's assassination. Other pictures — candids and execution shots — capture the killers and not the killed. Still others are novelties, such as Harvey Glatman's snapshots of terrified women he had tied up and would soon slay. This book's knockout visual punch is undermined by a slick, show-offy text that aims to be both arch and elegiac at once -- a feat the author does not pull off.

Head Shot, by Burl Barer. (Pinnacle, 2001): Telling, at a steady clip, the story of two 1984 murders in Tacoma, Wash., Barer gives the nuts and bolts but also goes a bit beyond. Not without sympathy, he delves into the killers' childhoods, unveiling incest, emotional abuse, and religion gone wrong. Interviews with nephews and ex-wives yield intriguing tidbits, but it all adds up to a crime so achingly pointless that sometimes the reader just wants to turn away. Pure stupidity motivated these killings, which took place in an alcoholic haze and were interesting only for their could-be-anyone randomness and their perpetrators' bumbling ineptitude. The book's graphic photographs demand repeat viewings, as the contrast between the killers' dull stares and the condition of their victims says more than words ever could.

The Shark Net, by Robert Drewe. (Penguin, 2001): For Australian novelist Drewe, the task of writing his memoirs was inextricably intertwined with writing a true-crime story. Set in gloriously sunny Perth, these reflections on a boyhood spent swimming in shark-infested surf and learning about sex comprise a glowingly frank and funny journey of self-discovery. Yet amid its scenes of family outings and making out are dark episodes in which we enter the world of a serial killer who was, during those years, terrorizing the peaceful seaside town. Deft pacing keeps both narratives aloft as we learn, but not a second too soon, how and why they're linked. The killings aren't this book's main concern, but in showing how they shaped a young writer's life, Drewe does something rare with their power and strangeness.

Hollywood Death Scenes, by Corey Mitchell. (Olmstead Press, 2001): Misspelled names pop up here and there throughout this well-intended but clumsily written new book, and each error is like another tiny crack in its veracity. Inept phrasings and Mitchell's inability to grasp the past-perfect tense will make some readers wince. Then, too, the title is pure bait-and-switch: as any Angeleno will gladly tell you, far-flung burgs such as Oxnard (way north of town) and Fullerton (way south) are so un-Hollywood that they might as well be in another state. And a fair portion of the 80-plus deaths recorded here are those of ordinary folks who had nothing to do with that realm which the author renders, painfully, as "Tinsletown." Still, these bite-size accounts offer easy access, complete with addresses and photographs, to nearly 100 different crimes. Many of these — the Manson, Menendez and Black Dahlia murders, for instance — are world-famous, making this book a new, if problematic, take on that Hollywood standby: a map to stars' homes.

Dark Dreams: Sexual Violence, Homicide, and the Criminal Mind, by Roy Hazelwood and Stephen G. Michaud. (St. Martin's Press, 2001): The craft of creating psychological profiles has, over the last few years, spawned its own array of books. An FBI alum, Hazelwood is an expert on sexual crime, and here he uses anecdotes of actual incidents to illustrate profiling techniques and strategies that are the mainstay of his work. Written in unpretentious, plain prose, the anecdotes still manage to be hair-raisingly evocative; alongside them, the strategy segments have a dry and near textbooklike feel. Still, the insights provided in this book are invaluable to all readers for whom the psychological side of crime is its most interesting side. As Hazelwood shows again and again, what motivates the perpetrators isn't always what you'd expect.

(Vol. 1, Dec. 10, 2001)

The Gates of Janus by Ian Brady. (Feral House, 2001): This is an insider's look at the criminal mind by quite possibly the most hated man in Britain. Ian Brady -- a sexual sadist and a fervent admirer of Adolf Hitler -- was apprehended with his girlfriend Myra Hindley in 1965 after the pair had abducted and murdered five youngsters and buried their bodies in the moors outside Manchester. In the Beatles' England, a storm of tabloid headlines dubbed Brady and Hindley "the Monsters of the Moors." Today they're serving life sentences. Brady begins The Gates of Janus with a rather droning analysis of serial murder. Then he offers lively and conversational-like profiles of notorious killers on both sides of the Atlantic, shedding new light on the likes of Ted Bundy and Richard Ramirez, even if you've read about them before. The author knew some of his subjects personally. British poisoner Graham Young used to play chess with Brady behind bars - though Young, as Brady brags, "always failed to win."

For an account of the Brady/Hindley killings, check out Emlyn Williams' classic, Beyond Belief (Random House, 1968). Beautifully written by a Welsh actor and playwright --Williams also wrote about Dr. Crippen, the notorious English ear, nose and throat man who murdered his wife in 1910 -- this narrative brings alive a time and place much less cynical than our own, a time and place where kids gladly climbed into the cars of strangers who offered them rides home from the fair.

Twentynine Palms by Deanne Stillman, (Morrow, 2001): An evocative account of a 1991 double murder in a down-and-out California desert town where two party girls, one of them about to turn 16, were raped and stabbed to death by a U.S. Marine just home from the Gulf War. The murders launched Stillman on a 10-year research odyssey, an excursion into the desert's own peculiar landscape of meth labs and cheap hotels. Her descriptions of sunbaked dunes and wasted lives make Twentynine Palms an elegy for all of those who dance so fast that they don't realize they're in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Son of a Grifter by Kent Walker and Mark Schone. (Morrow, 2001): In 1998, the mother-and-son team of Sante and Kenneth Kimes Jr. were charged with murdering a New York City socialite whose multimillion-dollar mansion they were trying, with the help of a stun gun and forged documents, to steal. Now they've been extradited to California owing to an earlier murder that landed a family friend, dead, in a Los Angeles Dumpster. A spate of books, articles and TV programs about the case has revealed, in sixtysomething Sante, a con artist who could pass for Elizabeth Taylor and whose relentless nerve netted her a fortune, then felled her. In Son of a Grifter released in hardcover a few months ago and due out in paperback soon, Kimes's elder son Kent Walker, aided by journalist Mark Schone, recounts life, blow by knockout blow, with a mother who stole, smuggled, kept slaves, and scammed her way into tête-à-têtes with Pat Nixon and Gerald Ford before moving on to murder. Love and regret tangle with fury as, confessing his own roles in some of Sante's capers, Walker probes the emotional minefield in which criminals' relatives must dwell.

Shot in the Heart by Mikal Gilmore. (Anchor, 2001): A tour de force by the younger brother of executed killer Gary Gilmore. Mikal, a first-rate writer, recalls a wildly violent father whose dark secrets might have included a murder of his own.

The Dark Side by Mark Schreiber. (Kodansha, 2001): If a country's crimes offer clues about its culture, then Ted Kaczynski and Timothy McVeigh reveal more about us than we might wish. In The Dark Side, Tokyo-based American reporter Mark Schreiber traces 400 years' worth of Japanese mayhem, from hostage-taking samurai on a rampage to 1995's Aum Shinrikyo's subway attack. A lengthy section on early methods of arrest and execution is less exciting than the dozens of bite-size anecdotes that follow: poisoners, voyeurs, stranglers, anarchists and hold-up men add extra texture to the serene imagery presented to the outside world in scrolls and Mount Fuji postcards. One standout is a bank robber who, in 1948, posed as a doctor on an anti-dysentery campaign and dosed the staff with "medicine" that killed them as he grabbed the cash. Another is Sada Abe, who severed her lover's genitals and carried them with her until she was caught; a national celebrity, Abe inspired In the Realm of the Senses, a landmark 1976 art film that remains the last word on erotic obsession. You'll never keep sharp objects beside the bed again.