Originally published on Advocate.com May 07 2012

Originally published on Advocate.com May 07 2012

Last March, when gay 24-year-old Daniel Zamudio was beaten so severely, after having swastikas carved into his skin, that he died in the hospital three week s later, the brutal murder shocked Chileans and spurred the government there to fast-track Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT) antidiscrimination legislation. A lawyer for Zamudio’s family, Jaime Silva, told The Christian Science Monitor that the crime was “the most brutal attack we’ve seen since the days of the dictatorship.” As soon as news hit U.S. shores, Zamudio was being called South America’s Matthew Shepard, and his murder a stark reminder of the crimes that have shaken LGBT folks, especially in the U.S., over the last 50 years.

As more than 70 countries prepare to observe the International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia May 17, criminologists, activists, and survivors in many cities have been discussing ways to deal with crimes against — and occasionally by — LGBT folks. There have been more than 600 reports of murdered trans people in almost 50 countries since January 2008 (including killings this year in Detroit, D.C., Florida, and California), and there was an overall 13% increase (in 2010, the most recently recorded year) in violent crimes committed against LGBT or HIV-positive people, according to the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs. Some murders are so iconic they’re steeped in popular culture: Brandon Teena, murdered by his rapists in Nebraska in 1993; Angie Zapata, a trans woman killed by a transphobic boyfriend (Zapata’s murderer was later tried on hate crime charges, a first for a transgender victim). But there are others that slip under the radar: some in which victims’ families never find justice — like Martha Oleman, a lesbian killed in Sugarcreek Township, Ohio, in 1997, her murder part of the state’s cold case files — and others in which police action is swift but resolution remains murky.

While all crimes change the world, on the following pages are 12 LGBT crimes that won’t soon be forgotten, serving as a reminder of the enduring violence we face daily.

HOUSTON’S STONEWALL

On July 4, 1991, a 27-year-old Houston banker was murdered and his two friends injured by a group of 10 young men who attacked them with nail-studded wooden planks, a knife, and steel-toed boots outside Heaven, a gay bar in the city’s heavily LGBT Montrose district. Paul Broussard died several hours after the attack, and his death led to a flurry of gay protests in front of the home of Mayor Kathy Whitmire (at 2 a.m.), in the affluent Woodlands (where Queer Nation protested near the homes of many of the 10 attackers), and then later throughout the Montrose neighborhood.

On July 4, 1991, a 27-year-old Houston banker was murdered and his two friends injured by a group of 10 young men who attacked them with nail-studded wooden planks, a knife, and steel-toed boots outside Heaven, a gay bar in the city’s heavily LGBT Montrose district. Paul Broussard died several hours after the attack, and his death led to a flurry of gay protests in front of the home of Mayor Kathy Whitmire (at 2 a.m.), in the affluent Woodlands (where Queer Nation protested near the homes of many of the 10 attackers), and then later throughout the Montrose neighborhood.

The latter was the largest LGBT civil disobedience action in the city’s history. At the time, David Fowler, a founder of the local Queer Nation chapter, articulated what many felt: “This is Houston’s Stonewall. People have finally said, ‘We’re fed up, we’ve had enough, and we’re not going to take it anymore.’” At the time, City Council candidate Annise Parker was as surprised as others that LGBT protesters took to the streets in such volume; she told The Advocate, “Houston is not a city that supports protest well.” Within days of Broussard’s murder, all l5 members of Houston’s City Council (including ones who had opposed gay rights ordinances previously) voted for a resolution asking then-governor Ann Richards to put a hate-crimes bill on the legislature’s agenda.

All 10 men were convicted of the killing. Only one remains in prison today: Jon Buice, sentenced to 45 years in 1992. The coroner had determined that the stabbing — which Buice admitted to — was what ultimately killed Broussard. Buice has been up for parole several times, each time denied.

Broussard’s murder led to a long push for hate-crimes protections, which passed in Texas a decade after his death (but to this day still don’t cover transgender individuals). In the area where Broussard was killed, the Montrose Remembrance Garden was dedicated last year to the victims of anti-LGBT crimes in the area and as a means to foster peace and tolerance. According to the Dallas Voice, there have been 35 people killed in the neighborhood since a pastor’s gay teenage son was killed in 1979, including Aaron Scheerhoorn, who was stabbed in December 2010, escaped his attacker and sought refuge in a local gay club, and was turned away only to be found again by his attacker, who killed him.

THE HAMPTON ROADS KILLER

THE HAMPTON ROADS KILLER

From 1987 to 1996, 12 gay or bisexual men were strangled to death and dumped in an area of Virginia called Hampton Roads. All but one were found nude. Most had been strangled; the others were too decomposed for the cause of death to be determined. Of the victims, all were last seen at gay bars in Portsmouth or Norfolk. By 1997, the local gay community was up in arms over the lack of police attention to the crimes, but, said Shirley Lesser, executive director of Virginians for Justice, the general public was not.

“It’s not gay-friendly here,” she said. “There is not a public outcry to solve gay murders. Police resources are dependent on where the public wants those resources to go.”

On May 6, 1997, police arrested Jackson Elton Manning for the murder of a gay man named Andrew “Andre” Smith, the most recent of the victims, who had been found strangled by a ligature and dumped in the Hampton Roads area. DNA evidence showed Manning had sex with Smith, and the victim’s blood — along with that of another victim, Reginald Joyner — was also found in Manning’s bed. In 1998, a jury sentenced Manning to life in prison for Smith’s murder, and Chesapeake police chief Richard Justice told reporters that Manning was the killer responsible for all 12 murders. Though Manning was never tried for the other 11 crimes, FBI documents later released to the public showed that the agency firmly believed the 42-year-old man was the Hampton Roads killer as early as 1996 — though his case caused profilers to rethink traditional victimology, as Manning, a black man, had both white and black victims, a rare modus operandi for a serial killer, the majority of whom target one racial group. After his arrest, there were no more similar crimes in the area.

A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME

A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME

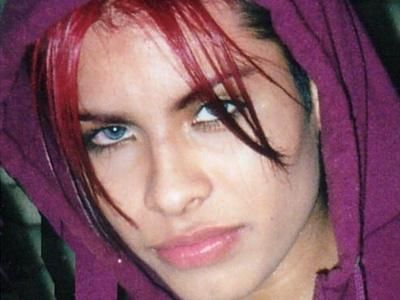

Gwen Amber Rose Araujo was an everyday teenager in many ways, a beautiful young woman who liked crop tops and blue jeans and lived in a small community in Northern California, dreaming of one day becoming a Hollywood makeup artist. But on October 3, 2002, she went to a party bravely wearing a miniskirt for the first time, and she never came home. The 17-year-old Araujo was transgender, and after Paul Merel's girlfriend discovered and outed Araujo at a party both girls were attending, four men — Michael William Magidson, 22, Jose Antonio Merel, 22, Jaron Chase Nabors, 19, and Jason Cezares, 22 — beat Araujo, slashed her face, hit her on the head with a shovel and a frying pan, strangled her, hogtied her, wrapped her body in a sheet, and tossed her into the back of a pickup truck. They drove her to a campground about 100 miles away in the Sierra foothills and dumped her body. Her mother didn’t know where she was for days, none of the partygoers reported the crime, and the media didn’t cover her disappearance until Nabors, traumatized by what had happened, led police to her gravesite.

Araujo had allegedly had anal or oral sex with two of the men in the weeks prior to the party; she was a regular friend of Merel’s who hung out at the house with other kids who drank and played dominoes. The men who killed her were all considered her friends.

She was certainly not the first trans woman or trans kid murdered, but her killing was shocking in part because of the extreme violence of the act and by the time and location where it occurred — in Newark, Calif., part of the Silicon Valley, just 30 miles from San Francisco. Her local high school was in the process of rehearsals for The Laramie Project, a play about the antigay murder of Matthew Shepard.

“In essence, the town of Newark lived through what Laramie did as the local school performed a play about the very same experience,” remembers Cathy Renna, the former news director of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. Gwen’s supportive and loving family stood up and demanded justice, Renna says, and with media attention, “good came from evil. To me, the most moving part of Gwen's story is her mother Sylvia [Guerrero]'s on-going fight for her child and her historic legal fight to have Gwen's birth certificate changed to female posthumously.” Guerrero told reporters that the tombstone would read Gwen, and that Araujo would be buried in the prettiest dress she could find.

After an initial mistrial, on September 12, 2005, Magidson and Merel were convicted of second-degree murder, but not convicted of the hate-crime enhancements. Nabors pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter in exchange for his testimony against the other killers; he got an 11-year prison sentence. Cazares, who insisted he wasn’t at the party at the time of the killing and said he only covered up the crime, eventually struck a deal with prosecutors and received a six-year sentence.

The San Francisco LGBT Community Center released a statement expressing the disappointment many felt upon hearing that the hate-crimes charges did not stick. “The jury did not see fit to find that these men were guilty of hate crimes. That hate did not play a role in this murder is unimaginable,” it read.

“This was a transgender youth who was interrogated, brutalized, sexually assaulted, and humiliated before her death, based upon her transgender status,” transgender musician and activist Shawna Virago told the Bay Area Reporter. She wanted community pushback after the verdict. “The overkill of the actual murder speaks to the fact that this was a hate crime. We have to remember that any of the freedom we enjoy in being out and expressing our gender comes from the fact that we have been fierce, and we have been proud, and very loud, and I don't see that right now.”

“Gwen being transgender was not a provocative act. She's who she was,” said Alameda County assistant district attorney Chris Lamiero, who prosecuted the case and had to battle at least one defendant’s “transgender panic” defense. “However, I would not further ignore the reality that Gwen made some decisions in her relation with these defendants that were impossible to defend. I don't think most jurors are going to think it's OK to engage someone in sexual activity knowing they assume you have one sexual anatomy when you don’t.”

The Gwen Araujo Justice for Victims Act (AB 1160) was signed into law September 28, 2006, by California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. It was the nation’s first bill to address the use of panic strategies, meaning defendants can’t use societal bias against their victim in order to decrease their own culpability for a crime.

Transgender Law Center represented Sylvia Guerrero in her petition to secure legal recognition of Gwen’s name change. Although requests for posthumous name changes are rare, attorneys with the center argued that the petition was a valid exercise of the court’s jurisdiction. In June of 2004, the same month the jury in Gwen’s murder trial deadlocked, the petition was granted and Gwen’s name was recognized.

THE HANDCUFF MAN

THE HANDCUFF MAN

For decades, bartenders, hustlers, and gay clubgoers in Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon corridor — an area where gay sex trade was common — circulated rumors about a mysterious man who mutilated and murdered young gay and bisexual men. There was talk of this urban legend, the Handcuff Man — as locals dubbed him — for years, and many swore that the man would offer men $50 to drink a pint of vodka, sometimes telling them he was studying the effects of alcohol. Often, the next thing the victim would know — assuming he lived — was that he had been dumped in a deserted area, handcuffed, his genitals set on fire. The attacks began in 1968. Many of the victims were afraid to report the crimes to the police, in part because being gay was still forbidden and because they were involved in shadow economies of street work. They were, in fact, easy targets for the Handcuff Man.

Over two decades after the attacks began, in May 1991, 21-year-old Michael Jordan was offered $50 to masturbate in a john’s car, then made to drink drug-laced vodka. Jordan did not regain consciousness until the next day at Grady Memorial Hospital, where he would stay nearly a month to undergo treatment severe burns to his thighs, groin, and buttocks. Jordan had been warned by a local bartender to stay away from a john that night; like many in the area’s gay community, Phoenix bartender Bill Adamson knew exactly who the Handcuff Man was. Jordan’s attack galvanized local lesbian and gay leaders, who then urged police to take the stories of the Handcuff Man seriously, at one point getting police captain Ken Boles to admit that they activists had a point, that the department’s sex crimes unit had been slow to respond (a day later, flacks said Boles was misquoted).

Wealthy local attorney Robert Lee Bennett was identified as the Handcuff Man, but before police made an arrest in the case, editors at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the city’s largest newspaper, agonized over whether to withhold the suspect’s name, as was their tradition, or to print it in the name of public safety. After numerous victims identified Bennett as the attacker, the editors decided to print his name. A day after they did, police in Tampa, Fla., requested Bennett’s information; later they charged him with an attack on Gary Clapp, a Florida man who had been burned so severely that both of his legs had to be amputated.

Prosecutors in Georgia and Florida negotiated a plea bargain for Bennett, in which he would plead guilty to the attempted murder of Gary Clapp as well as two counts of aggravated assault in Georgia, and could serve a concurrent 17-year sentence in Florida for all his crimes. LGBT activists were understandably outraged by the sentence, with Lynn Cothren, c-chair of Queer Nation, telling reporters at the time, “It’s a sad situation when people can get away with torture, intimidation, and hate. There’s obviously a problem with the system.”

Many hypothesized that Bennett’s sexual sadism was a result of his internalized homophobia (he didn’t admit to being gay until he was incarcerated), and he died in prison on April Fools’ Day in 1998.

LARAMIE’S GREAT LOSS

LARAMIE’S GREAT LOSS

So much has been written about the brutal murder of Matthew Shepard (who was killed the same year that James Byrd Jr. was murdered in an atrocious antiblack hate crime) that the facts of the case are already etched in many LGBT memories. Matthew Wayne Shepard was a 21-year-old student, a slight and friendly poli-sci major at the University of Wyoming. On October 6, 1998, Shepard met Russell Henderson and Aaron McKinney at a bar in Laramie, Wyo.; the men offered to drive Shepard home. Instead they drove to a desolate rural area where they tortured Shepard, robbed him, and tied him to a fence and left him to die. He was discovered some 18 hours later by a bicyclist who thought Shepard was a scarecrow. According to media reports and the book Illusive Shadows: Justice, Media, and Socially Significant American Trials, his face was completely covered in blood, except where tears had washed the blood away.

Taken to a hospital in nearby Fort Collins, Colo., Shepard remained in a coma for several days before he died of severe brain-stem damage, which shut down his internal organs and his heart; he also had fractures to the front and back of his head and numerous lacerations on his upper body from being pistol-whipped.

The murder was so shocking that candlelight vigils sprang up not just in Laramie but in larger cities like San Francisco and New York, and Shepard’s mother, Judy, became a champion of hate-crimes legislation. Because there was no hate-crime law nationally or in Wyoming at the time, neither of the killers could be charged with one, even though at least one had admitted to his girlfriend that the attack was spurred by his homophobia.

Both Henderson and McKinney asked their girlfriends to offer them alibis. On trial, McKinney tried to employ a gay panic defense, a sort of temporary insanity in response to an alleged sexual advance from the much smaller and unarmed victim. His girlfriend, however, told prosecutors that the two men “pretended they were gay to get him in the truck and rob him.”

Henderson made a plea deal for two consecutive life terms, while McKinney was found guilty of felony murder. Shepard’s parents interceded on McKinney’s behalf, saving him from the death penalty. His father, Dennis, told the Los Angeles Times that life in prison showed “mercy to someone who refused to show any mercy” for his son. McKinney received two life terms without possibility of parole.

While Fred Phelps, leader of the Westboro Baptist Church in Kansas, picketed Shepard’s funeral with signs that read “Fag Matt in Hell” and “No Tears for Queers,” the murder led to a sea change in how the public — from Hollywood to Peoria — viewed gay people as well as the need for sexual orientation and gender identity hate-crimes protections.

“Our nation, and our president at the time, was primed for dealing with this issue that was so long ignored,” says Renna. “It was 1998, just as the nation was having more and better national conversations about LGBT people — Ellen had just come out, our organizations were growing. and the Internet was becoming a powerful force for connection and action.”

Judy Shepard wrote a book in 2009, The Meaning of Matthew: My Son's Murder in Laramie, and a World Transformed, and she became one of the most visible activists pressing for change. A decade after Matthew's murder, in October 2009, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act passed Congress and was signed into law by President Barack Obama.

The first federal legislation to include LGBT people was just one of the changes that came from Shepard’s murder. Numerous artists recorded songs about Shepard and his murder (including Elton John, Trivium, Tori Amos, and Melissa Etheridge) and The Laramie Project (a play that became an HBO film, about the reaction of the town) has been performed in hundreds of locales around the globe.

“The Laramie Project and the work of the Shepard Foundation and Judy Shepard's relentless speaking out have been instrumental in creating the foundation upon which we stand in speaking about LBGT youth issues in general,” Renna says. “As someone who went to Laramie days after his body was discovered, was in Laramie when he died, sat through the plea bargain hearing of Russell Henderson and the trial of Aaron McKinney, worked with Tectonic Theater Project and HBO on countless performances and screenings of The Laramie Project, worked on the Epilogue (recently completed) and serve on the advisory board of the Shepard Foundation, there is no other issue that has more profoundly affected my life and the way I do my work day to day. It has informed my work and changed my life. Judy and Dennis Shepard's work and commitment are an inspiration to me and offer me a model for how to live my life as an activist and a parent.”

A TWO-SPIRIT TRAGEDY

A TWO-SPIRIT TRAGEDY

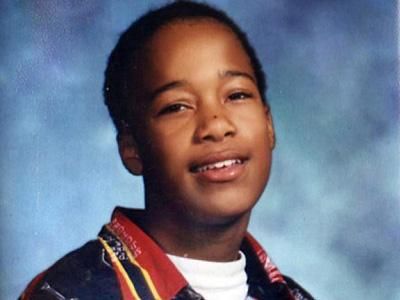

In the quiet of Cortez, Colo., in 2001, Fred “Frederica” C. Martinez Jr. — a 16-year-old transgender or “two-spirit” teen who loved Beyoncé so much he often went by her name — traveled to the Ute Mountain Roundup Rodeo. Five days later he was found dead in a sewer pond in a rocky canyon, an area the local teens call “the Pits,” his body decomposed and bludgeoned beyond recognition. Unlike with the Shepard murder, police and media attention was slow at first. Martinez’s mother, Pauline Mitchell, had called to report Martinez missing several times, but police didn’t return her calls until nearly 10 days after he disappeared.

Fred Martinez was a Native American two-spirit or nádleehí, what the Navajo call a male-bodied person with a feminine nature. He felt like a boy who was also a girl; a third gender that was both male and female. His family was accepting, and Martinez often dressed in feminine garb, a signature girl’s headband keeping wispy bangs out of his eyes. By all accounts from teachers, counselors, and friends, he was a healthy, happy, well-adjusted freshman at Montezuma-Cortez High School. But after the rodeo that night, Martinez met 18-year-old named Shaun Murphy at a party and accepted a ride from Murphy and one of his friends. The two dropped Martinez off, but he and Murphy met again later, and the reason has never been fully explained. Murphy later bragged that he had “beat up a fag.”

At the time, Martinez was the youngest person to die of a hate crime in the U.S. Murphy was later arrested and charged with second-degree murder, but both Mitchell and many victim advocates argued the local police should have investigated sooner and informed Mitchell of developments in the case. She reportedly read her child’s autopsy results in the local newspaper; it was the first she knew of the extent of his injuries, which included a slashed stomach, a fractured skull, and wounds to his wrists — and that he died from exposure and blunt trauma.

Murphy could not be charged with a hate crime because, at the time, Colorado’s hate-crime statutes did not cover crimes based on gender identity or expression. He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 40 years on June 4, 2002. Ironically, Murphy’s mother, an out lesbian, claimed the 18-year-old wasn’t homophobic, before leaving the courthouse in tears.

Mitchell put photos of Martinez in both male and female dress on his coffin at the funeral, and her unconditional acceptance and fierce love inspired many to rally around her.

“Fred's death had an indescribable impact on his family of course,” says Renna, “but has also changed the local school, police, and rest of the community. The school now has polices related to bullying based on sexual orientation and last I heard, a GSA. The biggest change is the increased attention to LGBT youth issues in general — not just hate crimes, but bullying, suicide, and family acceptance and rejection of youth coming out.”

Renna points to the unprecedented surge in exhaustive media coverage of transgender and gender-nonconforming children, says Renna, “that is informed by the conversations about Fred and the concept of two-spirit people and the Native American culture that gave us this deeply nuanced and spiritual way of looking at gender and sexual diversity. As someone who works on these issues every day, it has been deeply moving to see the lives of these children and youth spoken about and covered with compassion and accuracy.”

Martinez was further memorialized in the documentary Two Spirits, a film a decade in the making that aired in 90% of the country and broke PBS viewing records, and had special screenings attended by over 50,000 people in 100 cities nationwide. In just 19 days, 5,000 people commented on the film and over 2 million read about it on Facebook. The film, which introduces the two-spirit concept to thousands of people who had no awareness of Native traditions around gender, is also up for a GLAAD Award this year.

“Fred and Pauline's stories have moved the hearts and minds of thousands, and I have seen firsthand the impact of this film,” Renna says. “The way the First Nations and Native American LGBT/two-spirit communities embraced the film is, to those of us involved, a powerful affirmation of all of the hard work it took to bring Fred's story to the screen.”

HOOP DREAMS DASHED

HOOP DREAMS DASHED

Fifteen-year-old Sakia Gunn wasn’t unlike a lot of local teens. She loved to play baseball, got good grades, dreamed of playing in the WNBA, and spent time hanging out with friends. But Gunn, a junior at Newark, N.J.’s West Side High School, also identified as an Aggressive (or AG) — a gay butch woman of color who dresses in masculine clothes but doesn’t really identify as transgender or lesbian. Her girlfriend Jai was a femme.

On May 11, 2003, Gunn and her friends were waiting at a Newark bus stop after visiting New York’s Chelsea Piers along the Hudson River, an area where scores of young LGBT people would gather on the weekends. Two men in a vehicle pulled over and began asking the girls to come to their car. The girls told the men they weren’t interested in their sexual propositions because they were gay.

There was a police booth within shouting distance, but like many aging police booths — literally security stands, built after the 1960 riots, where police officers could look out and monitor the neighborhood activity — it wasn’t staffed that night. Newark, a heavily African-American city, is no stranger to violence, but Gunn and her friends had walked these roads before and were only minutes away from home.

But one of the men in the car, Richard McCullough, didn’t like rejection. According to Democracy Now, he jumped out of the vehicle and began choking one of the girls. Gunn and her friend Valencia* tried to stop him and Gunn hit McCullough. He turned and stabbed her in the chest before running back to the car and fleeing the scene.

A passing motorist gave the girls a ride to the hospital. Though reports differ, Gunn died in her friend’s arms either en route to or shortly after arriving at the local hospital. It was Mother’s Day.

Gunn’s friends created a makeshift memorial where she had been killed, and hundreds of lesbians showed up nightly. Nearly 3,000 people, many of them young queers, attended her funeral. Her death galvanized the local black queer community, and Laquetta Nelson used that mobilization to start the Newark Pride Alliance. “Sakia and her friends didn't mean anybody any harm that night,” she told reporters at the time. “They were coming back from having fun at the pier in New York, a place where they felt safe to be who they were.”

Lesbians nationwide, especially butch and masculine women, felt for Gunn. How many women had turned down sexual advances from men only to face violence?

“Sakia's murder was, in so many ways, the one that hit the closest to home,” says Renna. “As a self-identified AG, as a butch lesbian who has not infrequently been in the position she was — having men proposition or taunt a more feminine girlfriend or companion — I saw myself in this 15-year-old African-American youth from Newark. My heart broke when the New York community did not respond in nearly the way it did for Matthew Shepard, when Newark was a mere PATH train ride away. I was one of only a small handful of people who were not African-American at her funeral, and seeing the pain in the faces of the thousands. it pained me to not have the larger LGBT community gather in anger, protest, and grief as they did on the streets of Chelsea for Matt. I say this as one who was in Laramie for Matt.”

Indeed, the media, even the LGBT media, gave Gunn’s murder short shift. Professor Kim Pearson from the College of New Jersey did a study comparing media coverage of the Gunn case to 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard using the Lexis-Nexis database. She found that there were 659 stories in major newspapers about Shepard's murder, compared to only 21 articles about Gunn's murder in the seven-month period after their attacks. Pearson also reported that Shepard’s killers were arrested and convicted during that period, but it took almost that long for Gunn's killer to even be indicted.

One only had to do the math, Renna says, to understand why the lack of interest. “Poor. Person of color, gender-nonconforming. Who cares?” Renna says. “Well, we did, and while I was at GLAAD we fought for The New York Times and CNN to cover her death, which still haunts me, since I would have reacted in exactly the same way she did in her situation. Meeting another accepting and loving family who could not give voice to their grief was painful.”

Some local activists also indicted the black community of Newark, arguing that homophobia kept the mayor and black political leaders from doing more to help LGBT youth and from paying attention to a bias murder where both the victim and the perpetrator were black. Kelly Cogswell and Ana Simo asked in The Gully, “Where are the professionally outraged activists like Al Sharpton who always appear en masse to hold politicos accountable when young black people are cut down by hate and no one is doing anything? After all, he didn't let white censorship and racism stand in the way of protesting the murder of Amadou Diallo in New York, or Timothy Thomas hundreds of miles away in Cincinnati. The reason why Sakia Gunn was killed, and why her murder has faded from the headlines, is that both whites and blacks wish young black queers would disappear. Until things change, they will, thanks to violence, AIDS, and hate.”

As with Shepard, and Brandon Teena, Gunn’s life was memorialized on film in Dreams Deferred: The Sakia Gunn Film Project, a powerful doc that dissects both the homophobia that caused this murder and questions the lack of media coverage of her murder.

Today, that police booth on the corner near where Gunn was killed is staffed 24 hours a day, a promise former Newark mayor Sharpe James made in 2002.

* Last name withheld.

THE HANDSOMEST SERIAL KILLER

THE HANDSOMEST SERIAL KILLER

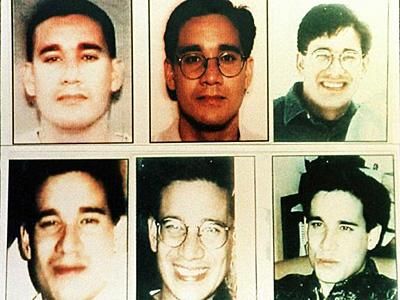

A handful of serial killers have been gay men with such internalized homophobia that they struck out at other men (e.g., John Wayne Gacy and Jeffrey Dahmer), but the case of Andrew Phillip Cunanan signaled a turning point in how police and the gay community worked together to prevent predation and capture predators.

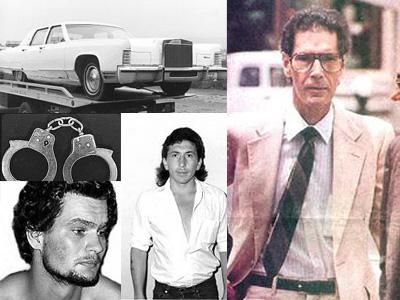

Cunanan was a swarthy, bright, and handsome young gay man who was intensely concerned about his appearance and status in life. As early as his teens, he was known to come up with fantastic tales about himself to impress his peers. A preppy son of a stockbroker, Cunanan moved after college to San Francisco’s Castro district, where he developed relationships with many sugar daddies who supported his lifestyle. He was no street hustler, though; Nicole Ramirez-Murray, a San Diego columnist who knew Cunanan, told The Washington Post that Cunanan modeled himself after Richard Gere in American Gigolo, even dressing like the character. His wealthy, older gay benefactors gifted him with cars, European vacations, and cash.

But youth is fleeting, and Cunanan began to lose his appeal — and his lovers. He started getting sick and had taken an HIV test but never returned for the results, instead convincing himself he was HIV-positive. He became depressed and reportedly let himself go physically after another of his lovers left him.

Jeffrey Trail and Cunanan dated when the two lived in San Diego. Trail was a closeted naval officer during “don’t ask, don’t tell.” When he moved to Bloomington, Minn., to manage a propane delivery company, Cunanan was reportedly heartbroken. On one visit he noticed that another of his former flames, David Madson, had also migrated to the Minneapolis area, and became convinced that Madson and Trail were lovers. After arguing on the phone with Trail, who denied the relationship, Cunanan told a bartender in San Francisco he would be out of town on some unfinished business, boarded a plane, and within hours, on April 25, 1997, he killed Trail with a heavy claw hammer during an argument in Madson’s apartment, where the latter two men had gathered to convince Cunanan nothing was going on. In shock, Madson helped Cunanan cover up the crime, but four days later, Cunanan drove Madson’s Jeep to a country road north of Minneapolis and put three bullets in his skull.

A few days later, Cunanan accosted 72-year-old Chicago developer Lee Miglin, a successful married man, in front of his home just moments after the neighbors saw Miglin standing alone. Police never ascertained whether Cunanan even knew this victim. TruTV reported that Cunanan marched Miglin into his own garage, bound his wrists, wrapped his face with duct tape “and proceeded to put him through a series of tortures lifted directly from what was said to be Andrew’s favorite ‘snuff’ film, Target for Torture. Pummeling him, kicking him, he then drove a pair of pruning shears into the man’s chest several times, muffling his screams. While Miglin still breathed, Andrew proceeded to slice his throat slowly with a hacksaw.” Afterward, Cunanan drove Miglin’s own Lexus over the body repeatedly.

The murder was so gruesome, it was clear that Cunanan was escalating. After Miglin’s murder the FBI added Cunanan to its Ten Most Wanted list. At this point, the LGBT communities in several cities were on edge, and reports of Cunanan sightings were sent in to police in multiple states. Posters of Cunanan were plastered across the Castro, Miami’s South Beach, and North Carolina’s gay nightclubs in Durham. It was rare for violence to come from within the gay community, and rarer still that the police and federal investigators were listening to gay complaints. After Miglin’s murder, many worried that Cunanan would return to San Francisco for the annual LGBT Pride Parade, and some people considered bowing out of the festivities, which attract hundreds of thousands. Turns out he was miles away.

Less than a week after Miglin’s murder, Cunanan killed 45-year-old William Reese at the Finn's Point National Cemetery in Pennsville, N.J., stealing his truck and leaving his last stolen vehicle there to taunt police and Reese’s bereaved widow, who found him. After that Cunanan headed to Miami, where he managed to evade police without seemingly trying, while going to gay clubs, hanging out at the beach and local tennis courts, and picking up men for occasional trysts.

Then, on July 15, 1997, Cunanan shot Gianni Versace outside the wealthy fashion design star’s home in South Beach and ran away as a witness tried but failed to tail him. There was no connection between the men, and forensic psychologists struggled to determine why Versace had been targeted. Many posited that perhaps Versace, a wealthy, glamorous, and attractive scion of Miami Beach, represented to Cunanan all that he wanted and believed he deserved but ultimately could never have. Versace’s murder led to a manhunt for Cunanan in Florida, and eight days later, as police closed in on a houseboat where Cunanan had been holed up, the serial killer used that same gun that killed Versace — stolen from his very first victim — to kill himself. He was 27.

THEIR OREGON TRAIL

THEIR OREGON TRAIL

When Roxanne Ellis and Michelle Abdill were found murdered in the back of their own pickup truck in southern Oregon, the media, their friends, and LGBT activists were quick to call the murder a hate crime. After all, the political climate in Oregon had been volatile for years, and the women — whom friends described as the ideal lesbian couple — had been active in the state’s bitter fights over two Oregon state ballot initiatives: Measure 9, a constitutional amendment that would have declared homosexuality "abnormal, wrong, unnatural and perverse," and Measure 19, which would have banned libraries from carrying material about homosexuality. The atmosphere in the Medford area was rife with tension as gay groups battled with religious groups fiercely through much of the ’90s.

But the women, both in their 50s and together 12 years, were in many respects, ordinary: respected local businesswomen who ran a property management company and spent their spare time restoring their Craftsman-style house, staying busy with their local church, and spoiling Ellis’s young granddaughter. That all changed on December 4, 1997, when Ellis went to an appointment with Robert Acremant, a 20-something young man, reportedly to show him an apartment for rent.

Ellis and Abdill were found four days later in the back of their pickup, both gagged and bound, shot in the head execution-style, covered with cardboard boxes. The news shocked the town, and as police searched for the killer, numerous organizations issued cautious press releases about the slayings, including the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, which said that “the women's outspoken stance on gay rights has inspired speculation that they might have fallen victim to a hate crime. Police have at least one report that they had been threatened.” Donna Red Wing, who at the time was a Portland-based GLAAD field director, said, "We don't know why Roxanne and Michelle were targeted. Was it because they were lesbian activists or because they were women? Was it a random act of violence? We don't have the answers yet.” The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force asked then-attorney general Janet Reno to have the Department of Justice work with Medford police because the killings should be considered hate crimes.

And yet many in the gay community and on the police force said activists were too quick to call these murders hate crimes. Acremant’s mother called the police saying she believed her son was responsible for the crimes, later telling The Oregonian that she called authorities “because I have to look God in the face. I will do anything in my power to make sure other people aren't hurt.”

After Acremant’s arrest, debate still raged over whether these murders were hate crimes; even The Advocate’s Inga Sorensen wrote about the aftermath of the murders, with a headline that read, “Rush to Judgment.” The killer reiterated repeatedly that the shootings had nothing to do with their sexual orientation, that he was simply robbing the women. But he also said he didn’t “care for lesbians” and believed the women’s lesbianism was sick.

“Bisexual women don't bother me a bit,” said Acremant in a later interview. “I couldn't help but think that [Ellis] is 54 years old and had been dating a woman for 12 years. Isn't that sick? That's someone's grandma, for God's sake. Could you imagine my grandma a lesbian with another woman? I couldn't believe that. It crossed my mind a couple of times — lesbo grandma. What a thing, huh?”

Lt. Tom Lavine of the Medford Police Department told Sorensen that local police considered the possibility that the killings were a hate crime right from the start and regretted telling NPR that antigay bias had nothing to do with them. “I sat up in bed that night and thought to myself, ‘What the heck did I say that for?’ I regret it now because Acremant's story was the weakest I have ever heard. It just didn't hold water. What ultimately motivated him to pull the trigger? We may never know.”

Acremant pleaded guilty to first-degree murder, and on October 27, 1997, he received the death sentence. In 2011, however, a judge reduced the sentence to life without parole after Acremant, who insists he hears voices in his head, was deemed too delusional to aid in his own appeals.

THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL ATTACKS

THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL ATTACKS

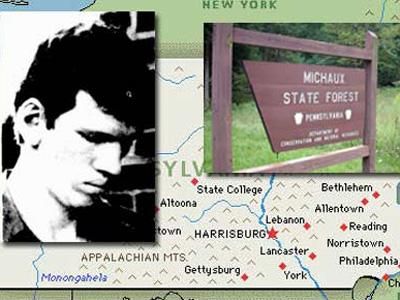

Rebecca Wright was a smart young woman, a mixed-race master’s degree student, who loved the outdoors and her girlfriend of two years, Claudia Brenner. The two had met at Virginia Tech, and although Wright lived with a boyfriend at the time the two women were still giddy with young love, albeit a closeted one. Brenner, an architecture student, and Wright decided to hike the Appalachian Trail in Pennsylvania, camping at Furnace State Park, part of the vast public lands that link the trail. The couple camped in an isolated wilderness area reveling in the privacy and the freedom to express themselves — that meant being nude, making love, and cuddling like young lovers. When Wright ran to deserted public restroom nearby on May 13, 1998, she encountered Stephen Ray Carr, a local mountain man who lived in a nearby cave. He was carrying a small rifle.

Spooked by his presence, the women left the campground to find a more private place to set up camp. They ran into Carr on the trail but finally thought they had ditched him. After setting up camp again and making sure they were alone, the two had sex. Unbeknownst to them, Carr was indeed watching. and moments later, Brenner felt bullets piercing her neck, face, arm, and head. Wright was shot too, in the head and back. As Wright collapsed she told Brenner to run for help, and the wounded woman — bleeding significantly from the five bullet wounds — would hike four miles and flag down two cars in order to get help.

Brenner was rushed to the hospital. She was still there when she learned that the police had found Wright, dead, laying exactly where she had been when she was shot. Carr’s bullet had pierced her liver. Brenner, who had never told police the two women were a couple, was left to grieve in silence.

By the time police found Carr — he had been hiding in a local Mennonite community, where locals didn’t have television and thus couldn’t recognize him — the killer had come up with multiple defenses, first saying his rifle was stolen, then at trial claiming that the women “taunted” him with their sexuality by making love in front of him. His attorney blamed his inexplicable rage on the couple’s lesbianism as well as two rapes he had suffered, as a child and later in a Florida prison.

The judge, though, refused to allow the women’s sexual relationship to be brought up in court — a rare and surprising move at the time when gay panic was still a valid defense — and Carr made a plea deal for life in prison almost exactly a year after Wright was killed. Brenner went on to become a crusader against anti-LGBT violence, and wrote a moving memoir of the events that killed her partner, Eight Bullets: One Woman’s Story of Surviving Anti-Gay Violence.

THE JENNY JONES MURDER

THE JENNY JONES MURDER

The competition among television talk shows in the 1990s was intense, each trying to goose ratings. The Jenny Jones Show certainly wasn’t immune to the pressure. Jones, an affable host, originally set out to do a more touchy-feely, Oprah-esque talk show, but when ratings never materialized, producers moved into terrain that would become ’90s talk show staples, like boot camp teens, confronted bullies, paternity tests, and secret crushes. It was on one such show on March 6, 1995, that Scott Amedure came on the show to confess his “secret crush” on Jonathan Schmitz, a man he knew from his former home in Michigan. Schmitz had assumed his secret admirer was a woman, and though he handled the taping of the show with what appeared to producers a natural aplomb, three days later he drove to Amedure’s home and shot him to death, then called 911 to confess.

There was plenty of speculation in the media, some suggesting Amedure’s sexual advances caused Schmitz to fly into a gay panic rage; others thought Schmitz acted out of internalized homophobia.

Many pointed the blame at Jones and her producers, and in 1999, Amedure’s family won a $25 million judgment against The Jenny Jones Show as well as Warner Bros. and Telepictures (which produced and distributed the show) for negligence in creating an atmosphere that led to Amedure’s murder. It was a verdict that victims’ advocates celebrated, but the Michigan Court of Appeals later overturned it.

At Schmitz’s trial, Amedure’s mother testified that her son had told her the two men had sex after taping the show. Schmitz was found guilty of second-degree murder in 1996, but the conviction was overturned, and he was tried a second time and again found guilty of the same charge. In 1999 he was sentenced to 25 to 50 years.

THE BYSTANDER EFFECT

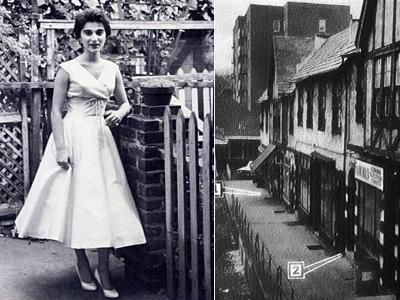

There’s a psychological phenomenon called the Bystander Effect, in which more people who are present at a crime, the less likely people are to help the victim of the crime. It applies both to crimes and other emergency situations. If there are few (or no) other witnesses to the crime, people act. The theory has been tested in a series of studies, but what led to those studies and the origination of the term (which is also called “Genovese syndrome”) was the brutal 1964 murder of a young New York lesbian named Kitty Genovese.

When 28-year-old Kitty Genovese got off work at Ev’s Eleventh Hour Bar it was already after 3 a.m., so she drove straight home to the apartment she shared with her partner, Mary Ann Zielonko, in the Kew Gardens section of Queens. She was heading toward her apartment door when Winston Moseley approached her. Clearly afraid, the slight young woman ran, but Moseley caught up with her and stabbed her from behind twice. Genovese screamed, shouting, “Oh, my God, he stabbed me! Help me!”

What happened next has been the subject of much debate, numerous botched newspaper reports, and psychological studies. Her cries were heard by several neighbors, and according to American Psychologist, one of them, Robert Mozer, yelled for Moseley to “Let that girl alone!” as the attacker was about to stab Genovese again.

As lights came on in nearby apartments, Moseley ran away to his vehicle, but as the lights went back off again, he got back out and began to follow Genovese, who had reached the doorway of her building. Police reports from that night are fuzzy; some say that the police didn’t take the calls seriously, and others say there was only one caller, nearly 30 minutes after the attack, who reported that a woman had been beaten but she was walking around.

Some newspapers reported the killer hid in his car, others reported that Moseley drove around until it was safe to return to his victim.

What’s not in dispute is that Moseley found Genovese and stabbed and raped her. Genovese had reached the doorway of her building and, according to The New York Times, cried out, “I’m dying.” Greta Schwartz heard those cries, called police, and ran to Genovese, holding her in her arms until the police arrived.

The Times reported that police discovered that 38 people had heard part of the attack on Genovese, and only one, Schwartz, had called police. Later, American Heritage analyzed the case and reported that only a dozen people had heard anything, most of them not realizing what was going on or the severity of the attack.

After the Times article came in 1964, psychologists dubbed this the first example of the bystander effect. But the article was said to be so sensationalized and inaccurate that in 2007, American Psychologist wrote that many modern psychology textbooks had gotten the facts of the case all wrong. While they called the case more of a parable, the editors didn’t dispute the bystander effect, which essentially boils down to the fact that people feel a diffusion of responsibility to act when in groups because they think someone else will. Feminist psychologists later tackled the case, saying that it was better viewed through the lens of male-female power dynamics rather than the bystander effect.

Kew Gardens historian Joseph De May analyzed the case for On the Media and reported that Genovese could not have screamed for the duration of her attack, saying the “wounds that she apparently suffered during the first attack, the two to four stabs in the back, caused her lungs to be punctured, and the testimony given at trial is that she died not from bleeding to death but from asphyxiation. The air from her lungs leaked into her thoracic cavity, compressing the lungs, making it impossible for her to breathe. I am not a doctor, but as a layman my question is, if someone suffers that type of lung damage, are they even physically capable of screaming for a solid half hour?”

The married Moseley was arrested and admitted he set out to kill Genovese because he wanted to kill a woman as women didn’t fight back; he admitted to two other rape-murders as well. He was initially found guilty and sentenced to death, but that was overturned and he was later given life. He has been denied parole 15 times so far.

Films, books, even the graphic novel Watchmen covered the Genovese case (Kitty is why Rorschach becomes a vigilante), though many works used that original and inaccurate New York Times report. Most recently, Steven Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner used the Genovese murder as a case study in the discussion of altruism in their best-selling SuperFreakonomics.

Links:

[1] http://www.advocate.com/

[2] http://www.amazon.com/Eight-Bullets-Surviving-Anti-Gay-Violence/dp/15634...

[3] http://www.onthemedia.org/2009/mar/27/the-witnesses-that-didnt/transcript/